Seven Years’ War;

Battle of Torgau

A.D. 1756-1763

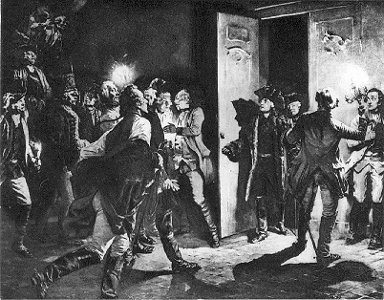

WOLFGANG MENZEL FREDERICK THE GREAT

In the Seven Years’ War Prussia stood practically alone against the united strength of all Europe; and it was the success of her King, Frederick, in withstanding the assaults of the vast and determined coalition that won him from the unanimous voice of military critics the title of the Great." The tremendous conflict, the most gigantic in Europe, between the Thirty Years’ War and the French Revolution, was the natural outcome of that earlier contest in which Frederick had seized Silesia. If this strong and able monarch was the type of the new spirit of doubt and endless questioning which had begun to permeate Europe, his chief antagonist, Maria Theresa, was no less emblematic of all that was noblest in the older, conservative Catholicism which Frederick defied. Maria Theresa never forgot her loss of Silesia. It was said of her that she could not see a Silesian without weeping, and with steady patience she set herself to draw all Europe into an alliance against Frederick.

Her rival’s caustic tongue helped her purpose. He gave personal offence not only to Elizabeth, the ruler of Russia, but to Madame Pompadour, the real sovereign of France under Louis XV. Both of these ladies urged their countries against the insulter. The three leading powers of continental Europe having thus leagued against Prussia, the lesser states soon coined them. Only England stood outside the coalition. Her war with France originating in the colonies and on the ocean, led her into an alliance with Prussia. But England was safe on her island, and few of her troops fought upon the Continent. She sent Frederick some money help; part of the time she kept the French troops from his frontier that was all.

The succession of Frederick’s remarkable battles are too numerous to detail. In one campaign he crushed the French at Rossbach, and over-threw the Austrians at Leuthen. Then he defeated the Russians at Zorndorf. Torgau was his last great triumph, and therefore his own account of that contest is here presented in connection with the concise narrative of the entire war by the standard German historian, Menzel. Frederick was a vigorous writer as well as a great fighter, and it is only air to caution the reader against accepting too fully the perhaps unconscious egotism of the monarch’s personal view. Some critics consider General Zieten the real winner of this battle.

WOLFGANG MENZEL

IN the autumn of 1756, Frederick, unexpectedly and without previously declaring war, invaded Saxony, of which he speedily took possession, and shut up the little Saxon army, thus taken unawares on the Elbe at Pima. A corps of Austrians, who were also equally unprepared to take the field, hastened, under the command of Browne, to their relief, but were, on October 1st, defeated at Lowositz, and the fourteen thousand Saxons under Rutowsky at Pirna were in consequence compelled to lay down their arms, the want to which they were reduced by the failure of their supplies having already driven them to the necessity of eating hair-powder mixed with gunpowder. Augustus III and Bruhl fled with such precipitation that the secret archives were found by Frederick at Dresden.

The Electress vainly strove to defend them by placing herself in front of the chest; she was forcibly removed by the Prussian grenadiers, and Frederick justified the suddenness of his attack upon Saxony by the publication of the plans of his enemies. He remained during the whole of the winter in Saxony, furnishing his troops from the resources of the country. It was here that his chamberlain, Glasow, attempted to take him off by poison, but, meeting by chance one of the piercing glances of the King, tremblingly let fall the cup and confessed his criminal design, the inducement for which has ever remained a mystery, to the astonished King.

The allies, surprised and enraged at the suddenness of the attack, took the field, in the spring of 1757, at the head of an enormous force. Half a million men were levied, Austria and France furnishing each about one hundred fifty thousand, Russia one hundred thousand, Sweden twenty thousand, the German empire sixty thousand. These masses were, however, not immediately assembled on the same spot, were, moreover, badly commanded and far inferior in discipline to the seventy thousand Prussians brought against them by Frederick. The war was also highly unpopular, and created great discontent among the Protestant party in the empire.

On the departure of Charles of Wuertemberg for the Imperial army, his soldiery mutinied, and, notwithstanding their reduction to obedience, the general feeling among the Imperial troops was so much opposed to the war that most of the troops deserted and a number of the Protestant soldiery went over to Frederick. The Prussian King was put out of the ban of the empire by th? Diet, and the Prussian ambassador at Ratisbon kicked the bearer of the decree out of the door.

Frederick was again the first to make the attack, and invaded Bohemia (1757). The Austrian army under Charles of Lorraine lay before Prague. The King, resolved at all hazards to gain the day, led his troops across the marshy ground under a terrible and destructive fire from the enemy. His gallant general, Schwerin, remonstrated with him. "Are you afraid?" was the reply. Schwerin, who had already served under Charles XII in Turkey and had grown gray in the field, stung by this taunt, quitted his saddle, snatched the colors, and shouted, "All who are not cowards follow me!" He was at that moment struck by several cartridge-balls and fell to the ground enveloped in the colors. The Prussians rushed past him to the attack.

The Austrians were totally routed; Browne fell, but the city was defended with such obstinacy that Daun, one of Maria Theresa’s favorites, was meanwhile able to levy a fresh body of troops. Frederick consequently raised the siege of Prague and came upon Daun at Kolin, where he had taken up a strong position. Here again were the Prussians led into the thickest of the enemy’s fire, Frederick shouting to them, on their being a third time repulsed with fearful loss, "Would ye live forever?" Every effort failed, and Benkendorf’s charge at the head of four Saxon regiments, glowing with revenge and brandy, decided the fate of the day. The Prussians were completely routed. Frederick lost his splendid guard and the whole of his luggage. Seated on the verge of a fountain and tracing figures in the sand, he reflected upon the means of realluring fickle Fortune to his standard.

A fresh misfortune befell him not many weeks later. England had declared in his favor, but the incompetent English commander, nicknamed, on account of his immense size, the Duke of Cumberland, allowed himself to be beaten by the French at Hastenbeck and signed the shameful Treaty of Closter Seven by which he agreed to disband his troops.1

This treaty was confirmed by the British monarch. The Prussian general Lewald, who had merely twenty thousand men under his command, was, at the same time, defeated at Gross-Zagerndorf by an overwhelming Russian force under Apraxin. Four thousand men were all that Frederick was able to bring against the Swedes. They were, nevertheless, able to keep the field, owing to the disinclination to the war evinced by their opponents.

Autumn fell, and Frederick’s fortune seemed fading with the leaves of summer. He had, however, merely sought to gain time in order to recruit his diminished army, and Daun having, with his usual tardiness, neglected to pursue him, he suddenly took the field against the Imperialists under the Duke of Saxe-Hildburghausen and the French under Soubise. The two armies met on November 5, 1757, on the broad plain around Leipsic, near the village of Rossbach, not far from the scene of the famous encounters of earlier times. The enemy, three times superior in number to the Prussians, lay in a half-circle with a view of surrounding the little Prussian camp, and, certain of victory, had encumbered themselves with a numerous train of women, wigmakers, barbers, and modistes from Paris. The French camp was one scene of confusion and gayety.

On a sudden Frederick sent General Seydlitz with his cavalry among them, and an instant dispersion took place, the troops flying in every direction without attempting to defend themselves, some Swiss, who refused to yield, alone excepted. The Germans on both sides showed their delight at the discomfiture of the French. An Austrian coming to the rescue of a Frenchman who had just been captured by a Prussian, "Brother German," exclaimed the latter, "let me have this French rascal!" "Take him and keep him!" replied the Austrian, riding off. The scene more resembled a chase than a battle. The Imperial army (Reichsarmee) was thence nicknamed the "Runaway" (Reissaus) army. Ten thousand French were taken prisoners. The loss on the side of the Prussians amounted to merely one hundred sixty men. The booty chiefly consisted in objects of gallantry belonging rather to a boudoir than to a camp. The French army perfectly resembled its mistress, the Marquise de Pompadour.

Frederick the Great at the castle of Lissa: "Can one get a lodging here, too?"

The Austrians had meanwhile gained great advantages to the rear of the Prussian army, had beaten the King’s favorite, General Winterfeld, at Moys in Silesia, had taken the important fortress at Schweidnitz and the metropolis, Breslau, whose commandant, the Duke of Bevern-a collateral branch of the house of Brunswick-had fallen into their hands while on a reconnoitring expedition. Frederick, immediately after the battle of Rossbach, hastened into Silesia, and, on his march thither, fell in with a body of two thousand young Silesians, who had been captured in Schweidnitz, but, on the news of the victory gained at Rossbach, had found means to regain their liberty, and had set off to his rencounter.

The King, inspired by this reenforcement, hurried onward, and, at Leuthen, near Breslau, gained one of the most brilliant victories over the Austrians during this war. Making a false attack upon the right wing, he suddenly turned upon the left. "Here are the Wurtembergers," said he, "they will be the first to make way for us!" He trusted to the inclination of these troops, who were zealous Protestants, in his favor. They instantly gave way and Daun’s line of battle was destroyed. During the night he threw two battalions of grenadiers into Lissa, and, accompanied by some of his staff, entered the castle, where, meeting with a number of Austrian generals and officers, he civilly saluted them and asked, "Can one get a lodging here, too ?" The Austrians might have seized the whole party, but were so thunderstruck that they yielded their swords, the King treating them with extreme civility.

Charles of Lorraine, weary of his unvarying ill-luck, resigned the command and was nominated stadtholder of the Netherlands, where he gained great popularity. At Leuthen twenty-one thousand Austrians fell into Frederick’s hands; in Breslau, which shortly afterward capitulated, he took seventeen thousand more, so that his prisoners exceeded his army in number.

Fresh storms rose on the horizon and threatened to overwhelm the gallant King, who, unshaken by the approaching peril, firmly stood his ground. The Austrians gained an excellent general in the Livonian, Gideon Laudon, whom Frederick had refused to take into his service on account of his extreme ugliness, and who now exerted his utmost endeavors to avenge the insult. The great Russian army, which had until now remained an idle spectator of the war, also set itself in motion. Frederick advanced in the spring of 1758 against Laudon, invaded Moravia, and besieged Oimuetz, but without success; Laudon ceaselessly harassed his troops and seized a convoy of three hundred wagons. The King was finally compelled to retreat, the Russians, under Fermor, crossing the Oder, murdering and burning on their route, converting Kuestrin, which refused to yield, into a heap of rubbish, and threatening Berlin. They were met by the enraged King at Zorndorf.

Although numerically but half as strong as the Russians, he succeeded in beating them, but with the loss of eleven thousand of his men, the Russians standing like walls. The battle was carried on with the greatest fury on both sides; no quarter was given, and men were seen, when mortally wounded, to seize each other with their teeth as they rolled fighting on the ground. Some of the captured Cossacks were presented by Frederick to some of his friends with the remark, "See with what vagabonds I am reduced to fight!" He had scarcely recovered from this bloody victory when he was again compelled to take the field against the Austrians, who, under Daun and Laudon, had invaded Lusatia. He for some time watched them without hazarding an engagement, under an idea that they were themselves too cautious and timid to venture an attack. He was, however, mistaken. The Austrians surprised his camp at Hochkirch during the night of October 14th. The Prussians-the hussar troop of the faithful Zieten, whose warnings had been neglected by the King, alone excepted-slept, and were only roused by the roaring of their own artillery, which Laudon had already seized and turned upon their camp.

The excellent discipline of the Prussian soldiery, nevertheless, enabled them, half naked as they were, and notwithstanding the darkness of the night, to place themselves under arms, and the King, although with immense loss, to make an orderly retreat. He lost nine thousand men, many of his bravest officers, and upward of a hundred pieces of artillery. The principal object of the Austrians, that of taking the King prisoner or of annihilating his army at a blow, was, however, frustrated. Frederick eluded the pursuit of the enemy and went straight into Silesia, whence he drove the Austrian general, Harsch, who was besieging Neisse, across the mountains into Bohemia. The approach of winter put a stop to hostilities on both sides.

During this year Frederick received powerful aid from Ferdinand, Duke of Brunswick, brother to Charles, the reigning Duke, who replaced Cumberland in the command of the Hanoverians and Hessians, with great ability covered the right flank of the Prussians, manoeuvred the French, under their wretched general, Richelieu, who enriched himself with the plunder of Halberstadt, across the Rhine, and defeated Clermont, Richelieu’s successor, at Crefeld. His nephew, the Crown Prince Ferdinand, served under him with distinction.

Toward the conclusion of the campaign an army under Broglio again pushed forward and succeeded in defeating the Prince von Ysenburg, who was to have covered Hesse with seven thousand men at Sangerhausen; another body of troops under Soubise also beat Count Oberg, on the Lutterberg. The troops on both sides then withdrew into winter quarters. The French had, during this campaign, also penetrated as far as East Friesland, whence they were driven by the peasantry until Wurmser of Alsace made terms with them and maintained the severest discipline among his troops.

The campaign of 1759 was opened with great caution by the allies. The French reenforced the army opposed to the Duke of Brunswick, and attacked him on two sides, Broglio from the Main, Contades from the Lower Rhine. The Duke was pushed back upon Bergen, but nevertheless gained a glorious victory over the united French leaders at Minden. His nephew, the Crown Prince Ferdinand, also defeated another French army under Brissac, on the same day, at Herford. The Imperial army, commanded by its newly nominated leader, Charles of Wurtemberg, advanced, but was attacked by the Crown Prince, while its commander was amusing himself at a ball at Fulda, and ignominiously put to flight.

Frederick, although secure against danger from this quarter, was threatened with still greater peril by the attempted junction of the Russians and Austrians, who had at length discovered that the advantages gained by Frederick had been mainly owing to the want of unity in his opponents. The Russians under Soltikoff, accordingly, approached the Oder. Frederick, at that time fully occupied with keeping the main body of the Austrians under Daun at bay in Bohemia, had been unable to hinder Laudon from advancing with twenty thousand men for the purpose of forming a junction with the Russians. In this extremity he commissioned the youthful general, Wedel, to use every exertion to prevent the further advance of the Russians. Wedel was, however, overwhelmed by the Russians near the village of Kay, and the junction with Laudon took place.

Frederick now hastened in person to the scene of danger, leaving his brother, Henry, to make head against Daun. On the banks of the Oder at Kunersdorf, not far from Frankfort, the King attempted to obstruct the passage of the enemy, in the hope of annihilating him by a bold manoeuvre, which, however, failed, and he suffered the most terrible defeat that took place on either side during this war (August 12, 1759). He ordered his troops to storm a sand-mountain, bristling with batteries, from the bottom of the valley of the Oder; they obeyed, but were unable to advance through the deep sand, and were annihilated by the enemy’s fire. A ball struck the King, whose life was saved by the circumstance of its coming in contact with an etui in his waistcoat pocket. He was obliged to be carried almost by force off the field when all was lost. The poet Kleist, after storming three batteries and crushing his right hand, took his sword in his left hand and fell while attempting to carry a fourth.

Soltikoff, fortunately for the King, ceased his pursuit. The conduct of the Russian generals was, throughout this war, often marked by inconsistency. They sometimes left the natural ferocity of their soldiery utterly unrestrained; at others, enforced strict discipline, hesitated in their movements, or spared their opponent. The key to this conduct was their dubious position with the Russian court. The Empress, Elizabeth, continually instigated by her minister, Bestuzheff, against Prussia, was in her dotage, was subject to daily fits of drunkenness, and gave signs of approaching dissolution. Her nephew, Peter, the son of her sister, Anna, and of Charles Frederick, Prince of Holstein-Gottorp, the heir to the throne of Russia, was a profound admirer of the great Prussian monarch, took him for his model, secretly corresponded with him, became his spy at the Russian court, and made no secret of his intention to enter into alliance with him on the death of the Empress. The generals, fearful of rendering themselves obnoxious to the future emperor, consequently showed great remissness in obeying Bestuzheff’s commands.

Frederick, however, although unharassed by the Russians, was still doomed to suffer fresh mishaps. His brother, Henry, had, with great prudence, cut off the magazines and convoys to Daun’s rear, and had consequently hampered his movements. The King was, notwithstanding, discontented, and, unnecessarily fearing lest Daun might still succeed in effecting a junction with Soltikoff and Laudon, recalled his brother, and by so doing occasioned the very movement it was his object to prevent. Daun advanced; and General Finck, whom Frederick had despatched against him at the head of ten thousand men, fell into his hands. Shut up in Maxen, and too weak to force its way through the enemy, the whole corps was taken prisoner. Dresden also fell; Schmettau, the Prussian commandant, had, up to this period, bravely held out, notwithstanding the smallness of the garrison, but, dispirited by the constant ill-success, he at length resolved at all events to save the military chest, which contained three million dollars, and capitulated on a promise of free egress. By this act he incurred the heavy displeasure of his sovereign, who dismissed both him and Prince Henry.

Fortune, however, once more favored Frederick; Soltikoff separated his troops from those of Austria and retraced his steps. The Russians always consumed more than the other troops, and destroyed their means of subsistence by their predatory habits. Austria vainly offered gold; Soltikoff (persisted in his intention and merely replied, "My men cannot eat gold." Frederick was now enabled, by eluding the vigilance of the Austrians, to throw himself upon Dresden, for the purpose of regaining a position indispensable to him on account of its proximity to Bohemia, Silesia, the Mere, and Saxony. His project, however, failed, notwithstanding the terrible bombardment of the city, and he vented his wrath at this discomfiture on the gallant regiment of Bernburg, which he punished for its want of success by stripping it of every token of military glory.

The constant want of ready money for the purpose of recruiting his army, terribly thinned by the incessant warfare, compelled him to circulate a false currency, the English subsidies no longer covering the expenses of the war, and his own territory being occupied by the enemy. Saxony consequently suffered, and was, owing to this necessity, completely drained, the town council at Leipsic being, for instance, shut up in the depth of winter without bedding, light, or firing, until it had voted a contribution of eight tons of gold; the finest forests were cut down and sold, etc.

Berlin meanwhile fell into the hands of the Russians, who, on this occasion, behaved with humanity. General Todleben even ordered his men to fire upon the allied troop, consisting of fifteen thousand Austrians, under Lacy and Brentano, for attempting to infringe the terms of capitulation by plundering the city. The Saxons destroyed the chateau of Charlottenburg and the superb collection of antiques contained in it, an irreparable loss to art, in revenge for the destruction of the palaces of Bruhl by Frederick. No other treasures of art were carried away or destroyed either by Frederick in Dresden or by his opponents in Berlin. This campaign offered but a single pleasing feature: the unexpected relief of Kolberg, who was hard pushed by the Russians in Pomerania, by the Prussian hussars under General Werner.

Misfortune continued to pursue the King throughout the campaign of 1760. Fouquet, one of his favorites, was, with eight thousand men, surprised and taken prisoner by Laudon in the Giant Mountains near Landshut; the mountain country was cruelly laid waste. The important fortress of Glatz fell, and Breslau was besieged. This city was defended by General Tauenzien, a man of great intrepidity. The celebrated Lessing was at that time his secretary. With merely three thousand Prussians he undertook the defence of the extensive city, within whose walls were nineteen thousand Austrian prisoners.

He maintained himself until relieved by Frederick. The King hastened to defend Silesia, for which Soltikoff’s procrastination allowed him ample opportunity. Daun had, it is true, succeeded in forming a junction with Laudon at Liegnitz, but their camps were separate, and the two generals were on bad terms. Frederick advanced close in their vicinity. An attempt made by Laudon, during the night of August 15th, to repeat the disaster of Hochkirch, was frustrated by the secret advance of the King to his rencounter, and a brilliant victory was gained by the Prussians over their most dangerous antagonist. The sound of the artillery being carried by the wind in a contrary direction, the news of the action and of its disastrous termination reached Daun simultaneously; at all events, he put this circumstance forward as an excuse, on being, not groundlessly, suspected of having betrayed Laudon from a motive of jealousy. He retreated into Saxony. The regiment of Bernburg had greatly distinguished itself in this engagement, and on its termination an old subaltern officer stepped forward and demanded from the King the restoration of its military badges, to which Frederick gratefully acceded.

Scarcely, however, were Breslau relieved and Silesia delivered from Laudon’s wild hordes than his rear was again threatened by Daun, who had fallen back upon the united Imperial army in Saxony and threatened to form a junction with the Russians then stationed in his vicinity in the Mere. Frederick, conscious of his utter inability to make head against this overwhelming force, determined, at all risks, to bring Daun and the Imperial army to a decisive engagement before their junction with the Russians, and, accordingly, attacked them at Torgau. Before the commencement of the action he earnestly addressed his officers and solemnly prepared for death. Daun, naturally as anxious to evade an engagement as Frederick was to hazard one, had, as at Collin, taken up an extremely strong position, and received the Prussians with a well-sustained fire.

A terrible havoc ensued; the battle raged with various fortune during the whole of the day, and, notwithstanding the most heroic attempts, the position was still uncarried at fall of night. The confusion had become so general that Prussian fought with Prussian, whole regiments had disbanded, and the King was wounded when Zieten, the gallant hussar general, who had during the night cut his way through the Austrians, who were in an equal state of disorder and had taken the heights, rushed into his presence. Zieten had often excited the King’s ridicule by his practice of brandishing his sabre over his head in sign of the cross, as an invocation for the aid of Heaven before making battle; but now, deeply moved, he embraced his deliverer, whose work was seen at break of day. The Austrians were in full retreat. This bloody action, by which the Prussian monarchy was saved, took place on November 3, 1760.

George II, King of England, expired during this year. His grandson, George III, the son of Frederick, Prince of Wales, who had preceded his father to the tomb, at first declared in favor of Prussia, and fresh subsidies were voted to her monarch by the English Parliament, which at the same time expressed "its deep admiration of his unshaken fortitude and of the inexhaustible resources of his genius." Female influence, however, erelong placed Lord Bute in Pitt’s stead at the helm of state, and the subsidies so urgently demanded by Prussia were withdrawn.

The Duke of Brunswick was, meanwhile, again victorious at Billinghausen over the French, and covered the King on that side. On the other hand, the junction of the Austrians with the Russians was effected in 1761; the allied army amounted in all to one hundred thirty thousand men, and Frederick’s army, solely consisting of fifty thousand, would in all probability have again been annihilated had he not secured himself behind the fortress of Schweidnitz, in the strong position at Bunzelwitz. Butterlin, the Russian general, was moreover little inclined to come to an engagement on account of the illness of the Empress and the favor with which Frederick was beheld by the successor to the throne. It was in vain that Laudon exerted all the powers of eloquence; the Russians remained in a state of inactivity and finally withdrew.

Laudon avenged himself by unexpectedly taking Schweid nitz under the eyes of the King by a clever coup-de-main, and had not a heroic Prussian artilleryman set fire to a powder-magazine, observing as he did so," All of ye shall not get into the town!" and blown himself with an immense number of Austrians into the air, he would have made himself master of this important strong-hold almost without losing a man. Frederick retreated upon Breslau.

The Empress Elizabeth expired in the ensuing year, 1762, and was succeeded by Peter III, who instantly ranged himself on the side of Prussia. Six months afterward he was assassinated, and his widow seized the reins of government under the title of Catharine II. Frederick was on the eve of giving battle to the Austrians at Reichenbach in Silesia, and the Russians under Czernichef were under his command, when the news arrived of the death of his friend and of the inimical disposition of the new Empress, who sent Czernichef instant orders to abandon the Prussian banner. Such was, however, Frederick’s influence over the Russian general that he preferred hazarding his head rather than abandon the King at this critical conjuncture, and, deferring the publication of the Empress’ orders for three days, remained quietly within the camp. Frederick meanwhile was not idle, and gained a complete victory over the Austrians (July 21, 1762).

The attempt made by a Silesian nobleman, Baron Warkotsch, together with a priest named Schmidt, secretly to carry off the King from his quarters at Strehlen, failed. In the autumn Frederick besieged and took Schweidnitz. The two most celebrated French engineers put their new theories into practice on this occasion: Lefevre, for the Prussians against the fortress; Griboval, for the Austrians engaged in its defence. Frederick’s good-fortune was shared by Prince Henry, who defeated the Imperial troops at Freiburg in Saxony, and by Ferdinand of Brunswick, who gained several petty advantages over the French, defeating Soubise at Wilhelmsthal and the Saxons on the Lutterbach. The spiritless war on this side was finally terminated during the course of this year (1762) by a peace between England and France.

Golz had at the same time instigated the Tartars in Southern Russia to revolt, and was on the point of creating a diversion with fifty thousand of them in Frederick’s favor. Frederick, with a view of striking the empire with terror, also despatched General Kleist into Franconia, with a flying corps, which no sooner made its appearance in Nuremberg and Bamberg than the whole of the South was seized with a general panic, Charles, Duke of Wurtemberg, for instance, preparing for instant flight from Stuttgard. Sturzebecher, a bold cornet of the Prussian hussars, accompanied by a trumpeter and by five-and-twenty men, advanced as far as Rothenburg on the Tauber, where, forcing his way through the city gate, he demanded a contribution of eighty thousand dollars from the town council. The citizens of this town, which had once so heroically opposed the whole of Tilly’s forces, were chased by a handful of hussars into the Bockshorn, and were actually compelled to pay a fine of forty thousand florins, with which the cornet scoffingly withdrew, carrying off with him two of the town councillors as hostages. So deeply had the citizens of the free towns of the empire at that time degenerated.

Frederick’s opponents at length perceived the folly of carrying on war without the remotest prospect of success. The necessary funds were, moreover, wanting. France was weary of sacrificing herself for Austria. Catharine of Russia, who had views upon Poland and Turkey, foresaw that the aid of Prussia would be required in order to keep Austria in check, and both cleverly and quickly entered into an understanding with her late opponent. Austria was, consequently, also compelled to succumb. The rest of the allied powers had no voice in the matter.

Peace was concluded at Hubertsburg, one of the royal Saxon residences, February 15, 1763. Frederick retained possession of the whole of his dominions. The machinations of his enemies had not only been completely frustrated, but Prussia had issued from the Seven Years’ War with redoubled strength and glory; she had confirmed her power by her victories, had rendered herself feared and respected, and had raised herself from her station as one of the principal potentates of Germany on a par with the great powers of Europe.

FREDERICK THE GREAT

The Russians entered Berlin the same day. It was agreed the citizens should, by tax, raise the sum of two millions, which should be paid in lieu of pillage. Generals Lacy and Czernichef were nevertheless tempted to burn a part of the city; and something fatal might have happened had it not been for the remonstrances of M. Verelst, the Dutch ambassador. This worthy republican spoke to them of the rights of nations, and depicted their fervidity in colors so fearful as to excite flame. Their fury and vengeance turned on the royal palaces of Charlottenburg and Schoenhausen, which were pillaged by the Cossacks and Saxons.

The rumor of the march of the King [Frederick] gained credit. Information was received by Lacy and Czernichef that he intended to cut off their retreat. This hastened their departure, and they retired on October 12th. The Russians repassed the Oder at Frankfort and Schwedt; and on the 15th Soltikoff marched toward Landsberg on the Warthe. Lacy pillaged whatever he could find on his route, and in three days regained Torgau. The Prince of Wurtemberg and Hulsen, embarrassed as to how to act, had turned toward Coswig, and cantoned there for want of knowing where to go.

At Gross-Morau the King heard these different accounts. As there were no more Russians to combat, he was at liberty to direct all his efforts against Saxony; therefore, instead of taking the route to Koepenick, he took that of Lueben. Marshal Daun, however, had followed the King into Lusatia. He then approached Torgau, and, as it was known that he had left Laudon at Loewenberg, General Goltz had orders to return into Silesia, to oppose the attempts of the Austrians with his utmost abilities. On the 22d the army of the King arrived at Jessen. The troops of the Prince de Deuxponts extended wholly along the left shore of the Elbe. He and the greatest part of his forces were at Prata, opposite Wittenberg; this fortress he evacuated as soon as the van of the Prussians appeared near the town.

The sudden changes that had happened during this campaign required new measures to be taken and other dispositions to be made. The Prussians had not a single magazine in all Saxony. The army of the King existed from day to day; he drew some little flour from Spandau, but this began to fail; add to this, the enemy occupied all Saxony. Daun had arrived at Torgau, the troops of the circles held the course of the Elbe, and the Duke of Wurtemberg occupied the environs of Dessau. To free himself from so many enemies, the King ordered Hulsen and the Prince of Wurtemberg to march to Magdeburg, there to pass the Elbe, and escort the boats loaded with flour which were to come to Dessau, where the King resolved to pass the Elbe with the right of his army, and afterward join Hulsen.

In the principality of Halberstadt the Prince of Wurtemberg had a rencounter with a detachment of the Duke, his brother, which was entirely destroyed. The Duke returned with all speed through Merseburg and Leipsic to Naumburg. The right of the King passed the Elbe on the 26th, and joined Hulsen and the Prince near Dessau. On this movement the Prince de Deuxponts abandoned the banks of the Elbe, and retired through Duben to Leipsic. He had left Ried in the rear, in a forest between Oranienbaum and Kemberg, where this officer had taken post, with little judgment; having garnished the woods with his hussars, and posted his pandoors in the plain.

The van of the Prussians attacked Ried; his scattered troops were beaten in detail and his corps almost destroyed. Of thirty-six hundred men he could only assemble one thousand seven hundred, at Pretsch, to which place he was driven after the action.

When the army of the King had obtained Kemberg, Zieten, who with the left had stopped the enemy at Wittenberg, passed the Elbe and joined the main army. Marshal Daun had, however, come up with Lacy at Torgau. As certain information was received that his vanguard had taken the road to Eulenburg, he could be supposed to have no other intention than that of joining the army of the circles. On this the army marched to Duben, to oppose a junction so prejudicial to the interests of the King.

Here arriving, a battalion of Croats was found, who were all either taken or put to the sword. At this place the King formed a magazine: it seemed the most convenient post because it is a peninsula and nearly surrounded by the Mulde. Some redoubts were constructed; and ten battalions under Sydow were left for its defence.

The army of the King thence marched to Eulenburg. The Austrian troops that had encamped in that vicinity retired, through Mochrena to Torgau, with so much precipitate haste that they abandoned a part of their tents. The army encamped with the right at Thalwitz and the left at Eulenburg. Hulsen was obliged to pass the Mulde with some battalions. He took a position between Belzen and Gostevra, opposite the Prince de Deuxponts, whose army was at Taucha. Under the present circumstances the first thing necessary was to drive the troops of the circles to a distance, as well because they were on the rear of the Prussians as to prevent their union with the Austrians. This cost but little trouble; Hulsen gave them the alarm, and they de-camped the same night, passed the Pleisse, and then the Elster, and retreated to Zeitz. Major Quintus, with his free battalion, vigorously charged their rear-guard; from which he took four hundred prisoners. After so happily terminating this expedition, the Prussians recovered possession of Leipsic, and Hulsen rejoined the army.

Every event hitherto (November) had turned to the advantage of the King. The irruption of the Russians and the taking of Berlin, which might appear to induce consequences so great, ended in a manner less afflicting than could have been expected. Contributions and money only were lost. The enemy was driven from the frontiers of Brandenburg. Wittenberg and Leipsic were recovered; and the troops of the circle were repulsed to a distance too considerable for it to be feared they should join the Imperialists with promptitude; but all was not yet done, and the projects that remained were the most difficult part of the whole.

The Russians kept at Landsberg on the Wartha and there might remain peaceful spectators of what should pass in Saxony. The King, however, was informed that other reasons engaged them not to march to too great a distance; for their design was, should the Austrians obtain any advantages over the army of the King, or should Marshal Daun maintain Torgau, to reenter the electorate of Brandenburg, and, conjointly with the Austrians, to take up their quarters on the banks of the Elbe. The consequence of such a project would have been fatally desperate to Prussia. By this position they would cut off the army, not only from Silesia and Pomerania, but from Berlin itself-that nursing mother which supplied clothing, arms, baggage, and every necessary for the men. Add to which the troops would have no quarters to take except beyond the Mulde, between the Pleisse, the Saale, the Elster, and the Unstrut. This would have been a space too narrow to supply the army with subsistence through the winter. And whence should magazines for the spring, uniforms, and recruits be obtained?

The army thus pressed, and thrown back upon the allies, would have starved them by starving itself.

Without any profound military knowledge every rational man would comprehend that, had the King remained quiet during autumn, and formed no new attempts, he would but have delivered himself, tied hand and foot, into the power of the enemy. Let us still further add that the provisions that had been deposited at Duben scarcely would supply the troops for the space of a month; that the frost, which began to be felt, would soon impede the navigation of the Elbe; consequently the boats could no longer bring provisions from Magdeburg; and, in fine, that the very last distress must have succeeded had not good measures been taken to remove the enemy, and gain ground on which the army might encamp and subsist.

After having maturely examined and weighed all these reasons, it was determined to commit the fortune of Prussia to the issue of a battle, if no other means by manoeuvring could be found of driving Marshal Daun from his post at Torgau. It will be proper to observe that the fears with which he might be inspired could only relate to two objects: the first, that of gaining Dresden before him, in which there was but a feeble garrison; and the second, of approaching the Elbe and disturbing him concerning subsistence, which was brought from Dresden by the river. It must be confessed that this last manoeuvre could not give him much uneasiness, because he was entirely master of the right shore of the Elbe, and might bring the provisions he wanted by land when they could no more be transported by water.

The greatest difficulty in executing this plan was that two things nearly contradictory were to be reconciled: the march of the army to the Elbe, and the security of the magazine. Not to forget all rule, the army of the King, in advancing, ought not to depart too far from the line of defence by which it covered its subsistence; and the motion it was to make upon the Elbe threw it entirely to the right and uncovered its rear. It was still endeavored to reconcile this enterprise on the enemy with the security of the magazine. The King proposed to incline to Schilda, that he might prove the countenance of Daun, and attack him at Torgau should he obstinately persist in remaining there. As it was but one march to Schilda, should the marshal retire on this motion, there was no fear that he should attempt Duben, and, if he remained at Torgau, by attacking him on the morrow, it seemed apparent that he would have so many occupations he would have no time to form projects against the magazine.

Everything conspiring to confirm the King in his resolution, he, on November 2d, marched the army to Schilda. During the whole route he continued with the vanguard of the hussars, that he might observe to which side the advanced posts of the enemy retired as they were repulsed by the troops of the King. This did not long remain a subject of doubt. The detachments all withdrew to Torgau, except Brentano, who was attacked at Belgern, and taken in such a direction that he could only escape toward Strebla. Kleist took eight hundred prisoners. The army of the King encamped from Schilda through Probsthain to Langen-Reichenbach, and Marshal Daun remained firm and motionless at Torgau. There no longer was any doubt that he had received positive orders from his court to maintain his post at any price.

The following dispositions were made for the attack on the morrow. The right of the Imperialists was supported behind the ponds of Groswich; their centre covered the hill of Sueptitz; the left terminated beyond Zinna, extending toward the ponds of Torgau. Exclusive of this, Ried observed the Prussian army from beside the forest of Torgau. Lacy, with a reserve of twenty thousand men, covered the causeway and the ponds that lie at the extremity of the place where the Imperialists had supported their left. Still the ground on which the enemy stood wanted depth, and the lines had not an interval of above three hundred paces. This was a very favorable circumstance for the Prussians; because, by attacking the centre in front and rear, the foe would be placed between two fires, and could not avoid being beaten.

To produce this effect the King divided his army into two bodies. The one destined to approach from the Elbe, after having passed the forest of Torgau, was to attack the enemy in the rear, from the hill of Sueptitz; while the other, following the route of Eulenburg to Torgau, was to fix a battery on the eminence of Groswich, and at the same time attack the village of Sueptitz. These two corps, acting in concert, must necessarily divide the centre of the Austrians; after which it would be easy to drive the remnant toward the Elbe, where the ground was one continued gentle declivity, excellently advantageous to the Prussians, and must have procured them a complete victory.

The King began his march at the dawn of day, on the 3d, and was followed by thirty battalions and fifty squadrons of his left. The troops crossed the forest of Torgau in three columns. The route of the first line of infantry led through Mochrena, Wildenhayn, Groswich, and Neiden; the route of the second through Pechhutte, Jaegerteich, and Bruckendorf, to Elsnich. The cavalry that composed the third column passed the wood of Wildenhayn, to march to Vogelsang. Zieten at the same time led the right of the army, consisting of thirty battalions and seventy squadrons, and filed off on the road that goes from Eulenburg to Torgau. The corps headed by the King met with General Ried, posted at the skirts of the forest of Torgau, with two regiments of hussars, as many dragoons, and three battalions of pandoors. Some volleys of artillery were fired, and he fell back on the right of the Imperialists.

Near Wildenhayn there is a small plain in the forest, where ten battalions of grenadiers were seen, well posted, who affected to dispute the passage of the Prussians. They made some discharges of artillery on the column of the King, which were answered by the Prussians. A line of infantry was formed to charge, but they reclined toward their army. The hussars brought word at the same time that the regiment of St. Ignon was in the wood, between the two columns of infantry, and that it had even dismounted. It was incontinently attacked; and, as these dragoons found no outlet for escape, the whole regiment was destroyed. These grenadiers and this regiment were mutually to depart on an expedition against Dobein, and the commanding officer, St. Ignon, who was taken, bitterly complained that Ried had not informed him of the approach of the Russians. This trifling affair only cost the troops a few moments; they pursued their road, and the heads of the columns arrived, at one o’clock, on the farther side of the forest, in the small plain of Neiden.

Here were seen some dragoons of Bathiani, and four battalions, who coming from the village of Elsnich made some discharges of artillery at a venture and fired with their small arms. This no doubt was a motion of surprise, occasioned perhaps by having seen some Prussian hussars. They retired upon a height behind the defile of Neiden. In this place is a large marsh, which begins at Groswich and goes to the Elbe, and over which there is no other passage but two narrow causeways. Had this corps taken advantage of its ground there certainly would have been no battle. However determined the King might be to attack the Imperialists, such an attack would have become impossible: he must have renounced his project, and returned full speed to regain Eulenburg.

But it happened far otherwise; these battalions hastened to rejoin the army, to which they were invited by a heavy cannonade which they heard from the side of Zieten. The King supposed, as was very probable, that the troops of Zieten already were in action with the enemy. This induced him to pass the defile of Neiden with his hussars and infantry; for the cavalry which ought to have proceeded was not yet come up. The King glided into a little wood, and personally reconnoitred the position of the enemy. He judged there was no ground on which it was proper to form, in presence of the Austrians, but by passing this small wood, which would in some measure conceal his troops, and whence a considerable ravine might be gained, to protect the soldiers, while they formed, from the enemy’s artillery. This ravine was not indeed above eight hundred paces from the Austrian army; but the remainder of the ground, which from Sueptitz descended like a glacis to the Elbe, was such that, had the army here been formed, one-half must have been cut off before it could approach the enemy.

Marshal Daun scarcely could credit the report that the Prussians were marching to the attack; nor was it till after reiterated information that he ordered his second line to face about and that the greatest part of the artillery of the first line was brought to the second. Whatever precaution the King might take to cover the march of his troops, the enemy, who had four hundred pieces of artillery in battery, could not fail to kill many of his men. Eight hundred soldiers fell, and thirty cannon were destroyed, with their horses, train, and gunners, before the columns arrived at the place where they were to be put in order of battle. The King formed his infantry in three lines, each of ten battalions, and began the attack. Had his cavalry been present, he would have thrown two regiments of dragoons into a bottom, that was on the right of his infantry, to cover its flank; but the Prince of Holstein, whose phlegm was invincible, did not come up till an hour after the action had begun. According to the regulations that had been agreed on, the attacks were to be made at the same time, and the result ought to have been that either the King or Zieten should penetrate through the centre of the enemy at Sueptitz. But General Zieten, instead of attacking, amused himself for a considerable time with a body of pandoors, whom he encountered in the forest of Torgau. He next cannonaded the corps of Lacy, who as we have said was posted behind the ponds of Torgau. In a word, the orders were not executed; the King attacked singly, without being seconded by Zieten, and without his cavalry being present. This still did not prevent him from pursuing his purpose. The first line of the King left the ravine and boldly marched to the enemy; but the prodigious fire of the Imperial artillery, and the descent of the ground, were too disadvantageous. Most of the Prussian generals, commanders of battalions, and soldiers, were killed or wounded. The line fell back, and returned in some disorder. By this the Austrian carbineers profited, pursued, and did not retreat till they had received some discharges from the second line. This line also approached, was disturbed, and, after a more bloody and obstinate combat than the preceding, was in like manner repulsed. Buelow, who led it to the attack, was taken.

At length the much-expected Prince of Holstein and his cavalry arrived. The third line of the Prussians was already in action; the regiment of Prince Henry, attacking the enemy, was in turn charged by the Austrian cavalry, and supported by the hussars of Hund, Reitzenstein, and Prittwitz, against all the efforts of the enemy to break its ranks. The dreadful fire of the artillery of the Austrians had too hastily consumed the ammunition. They had left their reserve of cannon on the other side of the Elbe, and their close lines did not admit of ammunition-wagons to pass and make proper distribution to the batteries.

The King profited by the moment when their fire slackened, and ordered the dragoons of Bayreuth to attack their infantry. They were led on with so much valor and impetuosity by Buelow that, in less than three minutes, they took prisoners the regiments of the Emperor, Neuperg, Geisruck, and Imperial-Bayreuth. The cuirassiers of Spaen and Frederick at the same time made an assault on that part of the enemy’s infantry which was most to the right of the Prussians, put it to the rout, and brought back many prisoners. The Prince of Holstein was placed to cover the left flank of the infantry, which his right wing joined, and his left inclined toward the Elbe. The enemy soon presented himself before the Prince, with eighty squadrons; the right toward the Elbe, the left toward Zinna. O’Donnel commanded the Imperial cavalry. Had he resolutely attacked the Prince, the battle must have been lost without resource, but he was respectful of a ditch of a foot and a half wide, which those who skirmished were forbidden to pass. The enemy believed it to be considerable, because the Prussians made a pretence of fearing to cross it; and the Imperialists remained, in the presence of the Prince, inactive.

The dragoons of Bayreuth had just cleared the height of Sueptitz. The King sent thither the regiment of Maurice, which had not engaged, and a brave and worthy officer, Lestwitz, brought up a corps of a thousand men, which he had formed from the different regiments that had been repulsed in previous attacks. With these troops the Prussians seized on the eminence of Sueptitz, and there fixed themselves, with all the cannon they could hastily collect. Zieten at length, having arrived at his place of destination, attacked on his side. It began to be dark, and to prevent Prussians from combating Prussians, the infantry of Sueptitz beat the march. They were presently joined by Zieten; and scarcely had the Prussians begun to form with order on the ground before Lacy came up, with his corps, to dislodge the King’s forces. He came too late: he was twice repulsed. Offended at his ill-reception, at half-past nine he retired toward Torgau. The Prussians and Imperialists were so near each other, among the vineyards of Sueptitz, that many officers and soldiers, on both parts, wandering in the dark, were made prisoners after the battle was over and all was tranquil. The King himself, as he was repairing to the village of Neiden, as well to expedite orders relative to the victory as to send intelligence of it through Brandenburg and Silesia, heard the sound of a carriage near the army. The word was demanded, and the reply was "Austrian." The escort of the King fell on and took two field-pieces and a battalion of pandoors, that had lost themselves in the night. A hundred paces farther he came up with a troop of horse, that again gave the word "Austrian carbineers." The King’s escort attacked and dispersed them in the forest. Those who were taken related that they had lost their road with Ried in the wood, and that they had imagined the Imperialists remained masters of the field.

The whole forest that had been crossed by the Prussians before the battle, and beside which the King was then riding, was full of large fires. What these might mean no one could divine, and some hussars were sent to gain information. They returned, and related that soldiers sat round the fires, some in blue uniforms and others in white. As intelligence more exact was necessary, officers were then sent, who learned a very singular fact, of which I doubt whether any example in history may be found: The soldiers were of both armies, and had sought refuge in the woods, where they had passed an act of neutrality, to wait till fortune had decided in favor of the Prussians or Imperialists; and they had mutually agreed to follow the victorious party.

This battle cost the Prussians thirteen thousand men, three thousand of whom were killed, and three thousand fell into the enemy’s hands, during the first attacks, while the Austrians were victorious; Buelow and Finck were among these. The breast of the King was grazed by a ball, and the margrave, Charles, received a contusion: several generals were wounded. The battle was obstinately disputed by both armies; its fury cost the Imperialists twenty thousand men, eight thousand of whom were taken, with four generals. They lost twenty-seven pair of colors and fifty cannon. Marshal Daun was wounded at the commencement of the battle.

When the enemy saw the first line of the Prussians give ground, with hopes too frivolous, they despatched couriers to Vienna and Warsaw to announce their victory; but the same night they abandoned the field of battle, and crossed the Elbe at Torgau. On the morning of the following day (the 4th), Torgau capitulated to General Hulsen. The Prince of Wurtemberg was sent over the Elbe to pursue the foe, who fled in disorder: he augmented the number of prisoners already made. The Imperialists would have been totally defeated had not General Beck, who was not in the engagement, covered their retreat by posting his corps between Arzberg and Triestewitz, behind the Landgraben. It was wholly in the power of Daun to have avoided a battle. Had he placed Lacy behind the defile of Neiden, instead of the ponds of Torgau, which six battalions would have been sufficient to defend, his camp would have been impregnable, so great may the consequences be of the least inadvertency in the difficult trade of war.

When the Russians were informed of the fate of the day of Torgau, they retired to Thorn, where they crossed the Vistula. The army of the King, on the 5th, advanced to Strebla, and on the 6th to Meissen. The Imperialists had left Lacy on that side of the Elbe, that he might cover the bottom of Plauen before their arrival. He attempted to dispute the defile of Zehren with the vanguard; but, when he saw the cavalry in motion to turn him by Lommatsch, he fled to Meissen, where he crossed the Tripsche; but, in spite of the celerity of his march, his rear-guard was attacked, and lost four hundred men. The pursuit was continued that an attempt might be made, favored by the fears and disorder of the foe, to pass the bottom of Plauen with him and seize on this important post. But no diligence could accomplish this; the troops were two hours too late; for, on arriving at Ukersdorf, another corps of the enemy was discovered, that had already taken post at the Windberg, the right of which extended to the Trompeter Schloesgen. This was the corps of Haddick, who, with the Prince de Deuxponts, quitting Leipsic, had marched to Zeitz, and afterward to Rosswein. No sooner were they informed of the Imperial defeat at Torgau than they diligently advanced to cover Dresden before the Prussians could come up.

1 The Hanoverian nobility, who hoped thereby to protect their property, were implicated in this affair. They were shortly afterward well and deservedly punished, being laid under contribution by the French.