Battle of Bunker Hill

A.D. 1775

JOHN BURGOYNE JOHN R. JESSE JAMES GRAHAME

This action, which took place about two months after the Battle of Lexington, though resulting in the physical defeat of the Americans, proved for them a moral victory. As at Lexington and Concord, the colonial soldiers showed that they were prepared to stand their ground in defence of the cause which called them to arms, and Bunker Hill became a watchword of the Revolution. This event also made it clear that the contest must be fought out. Thenceforth the two sides in the war were sharply defined.

The immediate occasion of this battle was the necessity, as seen by the British general, Gage, of driving the Americans from an eminence commanding Boston. This elevation was one of several hills on a peninsula just north of the town and running out into the harbor. It was the intention of the Americans to seize and fortify Bunker Hill, but for some unexplained reason they took Breed’s Hill, much nearer Boston, and there the battle was mainly fought. Breed’s Hill is now usually called Bunker Hill, and upon it stands the Bunker Hill monument.

The following accounts of the battle are all from British writers; one is that of the English officer General Burgoyne, who was afterward defeated at Saratoga; another is by the English historical author Jesse, whose best work covers the reign of George III. The third is from James Grahame, a native of Glasgow, Scotland, who died in 1842, of whose History of America a high authority says: "The thoroughly American spirit in which it is written prevented the success of the book in England." The historian Prescott gave it high praise for accuracy and fairness.

JOHN BURGOYNE

NOW ensued one of the greatest scenes of war that can be conceived. If we look to the height, Howe’s corps, ascending the hill in face of intrenchments, and in a very disadvantageous ground, was much engaged; to the left the enemy, pouring in fresh troops by thousands over the land; and in the arm of the sea our ships and floating batteries, cannonading them. Straight before us a large and noble town1

in one great blaze; and the church-steeples, being timber, were great pyramids of fire above the rest. Behind us the church-steeples and heights of our own camp covered with spectators of the rest of our army which was-engaged; the hills round the country also covered with spectators; the enemy all in anxious suspense; the roar of cannon, mortars, and musketry; the crash of churches, ships upon the stocks, and whole streets falling together, to fill the ear; the storm of the redoubts, with the objects above described, to fill the eye; and the reflection that perhaps a defeat was a final loss to the British empire of America, to fill the mind, made the whole a picture and a complication of horror and importance beyond anything that ever came to my lot to witness.

JOHN HENFAGE JESSE

About 11 P.M. on June 16th a detachment of about a thousand men, who had previously joined solemnly together in prayer, ascended silently and stealthily a part of the heights known as Bunker Hill, situated within cannon range of Boston and commanding a view of every part of the town. This brigade was composed chiefly of husbandmen, who wore no uniform, and who were armed with fowling-pieces only, unequipped with bayonets. The person selected to command them on this daring service was one of the lords of the soil of Massachusetts, William Prescott, of Pepperell, the colonel of a Middlesex regiment of militia. "For myself," he said to his men, "I am resolved never to be taken alive." Preceded by two sergeants bearing dark-lanterns, and accompanied by his friends, Colonel Gridley and Judge Winthrop, the gallant Prescott, distinguished by his tall and commanding figure, though simply attired in his ordinary calico smock-frock, calmly and resolutely led the way to the heights. Those who followed him were not unworthy of their leader.

It was half-past eleven before the engineers commenced drawing the lines of the redoubt. As the first sod was being upturned, the clocks of Boston struck twelve. More than once during the night-which happened to be a beautifully calm and starry one-Colonel Prescott descended to the shore, where the sound of the British sentinels walking their rounds, and their exclamations of "All’s well!" as they relieved guard, continued to satisfy him that they entertained no suspicion of what was passing above their heads. Before daybreak the Americans had thrown up an intrenchment, which extended from the Mystic to a redoubt on their left. The astonishment of Gage, when on the following morning he found this important site in the hands of the enemy, may be readily conceived. Obviously not a moment was to be lost in attempting to dislodge them; and accordingly a detachment, under General Howe, was at once ordered on this critical service.

In the mean time a heavy cannonade, first of all from the Lively (sloop-of-war), and afterward from a battery of heavy guns from Copp’s hill, in Boston, was opened upon the Americans. Exposed, however, as they were to a storm of shot and shell, unaccustomed, as they also were, to face an enemy’s fire, they nevertheless pursued their operations with the calm courage of veteran soldiers.

Late in the day, indeed, when the scorching sun rose high in the cloudless heavens, when the continuous labors of so many hours threatened to prostrate them, and when they waited, but waited in vain, for provisions and refreshments, the hearts of a few began to fail them, and the word retreat was suffered to escape from their lips. There was among them, however, a master spirit, whose cheering words and chivalrous example never failed to restore confidence. On the spot-where now a lofty column, overlooking the fair landscape and calm waters, commemorates the events of that momentous day-was then seen, conspicuous above the rest, the form of Prescott of Pepperell, in his calico frock, as he paced the parapet to and fro, instilling resolution into his followers by the contempt which he manifested for danger, and amid the hottest of the British fire delivering his orders with the same serenity as if he had been on parade. "Who is that person ?" inquired Governor Gage of a Massachusetts gentleman, as they stood reconnoitring the American works from the opposite side of the river Charles. "My brother-in-law, Colonel Prescott," was the reply. "Will he fight ?" asked Gage. "Ay," said the other, "to the last drop of his blood."

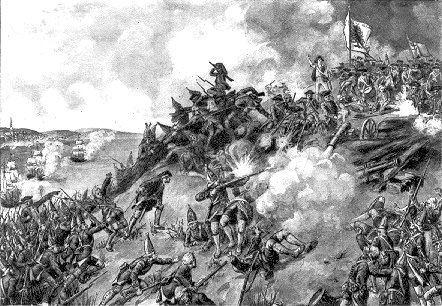

The Battle of Bunker Hill

It was after 3 P.M. when General Howe’s detachment, consisting of about two thousand men, landed at Charlestown and formed for the attack. Prescott’s instructions to his men, as the British approached, were sufficiently brief. "The red-coats," he said, "will never reach the redoubt if you will but withhold your fire till I give the order, and be careful not to shoot over their heads." In the mean time, ascending the hill under the protection of a heavy cannonade, the British infantry had advanced unmolested to within a few yards of the enemy’s works, when Prescott gave the word "Fire!" So promptly and effectually were his orders obeyed that nearly the whole front rank of the British fell. Volley after volley was now opened upon them from behind the intrenchments, till at length even the bravest began to waver and fall back; some of them, in spite of the threats and passionate entreaties of their officers, even retreating to the boats.

Minutes, many minutes apparently, elapsed before the British troops were rallied and returned to the attack, exposed to the burning rays of the sun, encumbered with heavy knapsacks containing provisions for three days, compelled to toil up very disadvantageous ground with grass reaching to their knees, clambering over rails and hedges, and led against men who were fighting from behind intrenchments and constantly receiving reenforcements by hundreds-few soldiers, perhaps, but British infantry would have been prevailed upon to renew the conflict. Again, however, they advanced to the charge; again, when within five or six rods of the redoubt, the same tremendous discharge of musketry was opened upon them; and again, in spite of many heroic examples of gallantry set them by their officers, they retreated in the same disorder as before.

By this time the grenadiers and light infantry had lost three- fourths of their men; some companies had only eight or nine men left, one or two had even fewer. When the Americans looked forth from their intrenchments the ground was literally covered with the wounded and dead. According to an American who was present, "the dead lay as thick as sheep in a fold." For a few seconds General Howe was left almost alone. Nearly every officer of his staff had been either killed or wounded. The Americans, who have done honorable justice to his gallantry, remarked that, conspicuous as he stood in his general officer’s uniform, it was a marvel that he escaped unhurt. He retired, but it was with the stern resolve of a hero to rally his men-to return and vanquish.

The third and last attack made by General Howe upon the enemy’s intrenchments appears to have taken place after a considerably longer interval than the previous one. This interval was employed by Prescott in addressing words of confidence and exhortation to his followers, to which their cheers returned an enthusiastic response. "If we drive them back once more," he said, "they cannot rally again." General Howe, in the mean time, by disencumbering his men of their knapsacks, and by bringing the British artillery to play so as to rake the interior of the American breastwork, had greatly enhanced his chances of success. Once more, at the word of command, in steady un-broken line, the British infantry mounted to the deadly struggle; once more the cheerful voice of Prescott exhorted his men to reserve their fire till their enemies were close upon them; once more the same deadly fire was poured down upon the advancing royalists. Again on their part there was a struggle, a pause, an indication of wavering; but on this occasion it was only momentary. Onward and headlong against breastwork and against vastly superior numbers dashed the British infantry, with a heroic devotion never surpassed in the annals of chivalry. Almost in a moment of time, in spite of a second volley as destructive as the first, the ditch was leaped and the parapet mounted.

In that final charge fell many of the bravest of the brave. Of the Fifty-second regiment alone, three captains, the moment they stood on the parapet, were shot down. Still the English infantry continued to pour forward, flinging themselves among the American militiamen, who met them with a gallantry equal to their own. The powder of the latter having by this time become nearly exhausted, they endeavored to force back their assailants with the butt-ends of their muskets. But the British bayonets carried all before them. Then it was, when further resistance was evidently fruitless, and not till then, that the heroic Prescott gave the order to retire. From the nature of the ground it was necessarily more a flight than a retreat. Many of the Americans, leaping over the walls of the parapet, attempted to fight their way through the British troops; while the majority endeavored to escape by the narrow entrance to the redoubt. In consequence of the fugitives being thus huddled together, the slaughter became terrific.

"Nothing," writes a young British officer, who was engaged in the melee, "could be more shocking than the carnage that followed the storming of this work. We tumbled over the dead to get at the living, who were crowding out of the gap of the re-doubt, in order to form under the defences which they had prepared to cover their retreat." Prescott was one of the last to quit the scene of slaughter. Although more than one British bayonet had pierced his clothes, he escaped without a wound.

That night the British intrenched themselves on the heights, lying down in front of the recent scene of contest. The loss in killed and wounded was ten hundred fifty-four. According to the American account their loss was one hundred forty-five killed and three hundred four wounded; of their six pieces of artillery, they only succeeded in carrying off one.

Such was the result of the famous Battle of Bunker Hill, a contest from which Great Britain derived little advantage beyond the credit of having achieved a brilliant passage of arms, but which, on the other hand, produced the significant effect of manifesting, not only to the Americans themselves, but to Europe, that the colonists could fight with a steadiness and courage which ere long might render them capable of coping with the disciplined troops of the mother-country.

JAMES GRAHAME

About the latter part of May, a great part of the reenforcements ordered from Great Britain arrived at Boston. Three British generals, Howe, Burgoyne, and Clinton, whose behavior in the preceding war had gained them great reputation, arrived about the same time. General Gage, thus reenforced, prepared for acting with more decision; but before he proceeded to extremities, he conceived it due to ancient forms to issue a proclamation, holding forth to the inhabitants the alternative of peace or war. He therefore offered pardon, in the King’s name, to all who should forthwith lay down their arms and return to their respective occupations and peaceable duties: excepting only from the benefit of that pardon "Samuel Adams and John Hancock, whose offences were said to be of too flagitious a nature to admit of any other consideration than that of condign punishment." He also proclaimed that not only the persons above named and excepted, but also all their adherents, associates, and correspondents, should be deemed guilty of treason and rebellion, and treated accordingly. By this proclamation it was also declared "that as the courts of judicature were shut, martial law should take place till a due course of justice should be reestablished."

It was supposed that this proclamation was a prelude to hostilities; and preparations were accordingly made by the Americans. A considerable height, by the name of Bunker Hill, just at the entrance of the peninisula of Charlestown, was so situated as to make the possession of it a matter of great consequence to either of the contending parties. Orders were therefore issued, by the provincial commanders, that a detachment of a thousand men should intrench upon this height. By some mistake, Breed’s Hill, high and large like the other, but situated nearer Boston, was marked out for the intrenchments, instead of Bunker Hill. The provincials proceeded to Breed’s Hill and worked with so much diligence that between midnight and the dawn of the morning they had thrown up a small redoubt about eight rods square. They kept such a profound silence that they were not heard by the British, on board their vessels, though very near. These having derived their first information of what was going on from the sight of the works, early completed, began an incessant firing upon them.

The provincials bore this with firmness, and, though they were only young soldiers, continued to labor till they had thrown up a small breastwork extending from the east side of the redoubt to the bottom of the hill. As this eminence overlooked Boston, General Gage thought it necessary to drive the provincials from it. About noon, therefore, he detached Major-General Howe and Brigadier-General Pigot, with the flower of his army, consisting of four battalions, ten companies of the grenadiers and ten of light infantry, with a proportion of field artillery, to effect this business. These troops landed at Moreton’s Point, and formed after landing, but remained in that position till they were reinforced by a second detachment of light infantry and grenadier companies, a battalion of land forces, and a battalion of marines, making in the whole nearly three thousand men. While the troops who first landed were waiting for this reenforcement, the provincials, for their further security, pulled up some adjoining post and rail fences, and set them down in two parallel lines at a small distance from each other, and filled the space between with hay, which, having been lately mowed, was found lying on the adjacent ground.

The King’s troops formed in two lines, and advanced slowly to give their artillery time to demolish the American works. While the British were advancing to the attack they received orders to burn Charlestown. These were not given because they were fired upon from the houses in that town, but from the military policy of depriving enemies of a cover in their approaches. In a short time this ancient town, consisting of about five hundred buildings, chiefly of wood, was in one great blaze. The lofty steeple of the meeting-house formed a pyramid of fire above the rest, and struck the astonished eyes of numerous beholders with a magnificent but awful spectacle. In Boston the heights of every kind were covered with citizens, and such of the King’s troops as were not on duty. The hills around the adjacent country, which afforded a safe and distinct view, were occupied by the inhabitants of the country.

Thousands, both within and without Boston, were anxious spectators of the bloody scene. Regard for the honor of the British army caused hearts to beat high in the breasts of many; while others, with keener sensibilities, sorrowed for the liberties of a great and growing country. The British moved on slowly, which gave the provincials a better opportunity for taking aim. The latter, in general, reserved their fire until their adversaries were within ten or twelve rods, and then began a furious discharge of small arms. The stream of the American fire was so incessant, and did so great execution, that the King’s troops retreated with precipitation and disorder. Their officers rallied them and pushed them forward with their swords; but they returned to the attack with great reluctance. The Americans again reserved their fire till their adversaries were near, and then put them a second time to flight. General Howe and the officers redoubled their exertions, and were again successful, though the soldiers displayed a great aversion to going on. By this time the powder of the Americans began so far to fail that they were not able to keep up the same brisk fire. The British then brought some cannon to bear, which raked the inside of the breastwork from end to end. The fire from the ships, batteries, and field artillery was redoubled; the soldiers in the rear were goaded on by their officers. The redoubt was attacked on three sides at once. Under these circumstances a retreat from it was ordered, but the provincials delayed so long, and made resistance with their discharged muskets as if they had been clubs, that the King’s troops, who had easily mounted the works, half filled the redoubt before it was given up to them.

While these operations were going on at the breastwork and redoubt, the British light infantry were attempting to force the left point of the former, that they might take the American line in flank. Though they exhibited the most undaunted courage, they met with an opposition which called for its greatest exertions. The provincials reserved their fire till their adversaries were near, and then discharged it upon the light infantry in such an incessant stream, and with so true an aim, as that it quickly thinned their ranks. The engagement was kept up on both sides with great resolution. The persevering exertions of the King’s troops could not compel the Americans to retreat till they observed that their main body had left the hill. This, when begun, exposed them to new dangers; for it could not be effected but by marching over Charlestown Neck, every part of which was raked by the shot of the Glasgow (man-of-war) and of two floating batteries. The incessant fire kept up across the Neck prevented any considerable reenforcement from joining their countrymen who were engaged; but the few who fell on their retreat over the same ground proved that the apprehensions of those provincial officers, who declined passing over to succor their companies, were without any solid foundation.

The number of Americans engaged amounted only to fifteen hundred. It was apprehended that the conquerors would push the advantage they had gained, and march immediately to American headquarters at Cambridge; but they advanced no farther than Bunker Hill. There they threw up works for their own security. The provincials did the same, on Prospect Hill, in front of them. Both were guarding against an attack; and both were in a bad condition to receive one. The loss of the peninsula depressed the spirits of the Americans; and the great loss of men produced the same effect on the British. There have been few baffles in modern wars in which, all circumstances considered, there was a greater destruction of men than in this short engagement.

The loss of the British, as acknowledged by General Gage, amounted to one thousand fifty-four. Nineteen commissioned officers were killed and seventy more were wounded. The Battle of Quebec, in 1759, which gave Great Britain the colony of Canada, was not so destructive to British officers as this affair of a slight intrenchment, the work only of a few hours. That the officers suffered so much must be imputed to their being aimed at. None of the provincials in this engagement were riflemen, but they were all good marksmen. The whole of their previous military knowledge had been derived from hunting and the ordinary amusements of sportsmen. The dexterity which by long habit they had acquired in hitting beast, birds, and marks, was fatally applied to the destruction of British officers. From their fall, much confusion was expected. They were therefore particularly singled out. Most of those who were near the person of General Howe were either killed or wounded; but the General, though he greatly exposed himself, was unhurt. The light infantry and grenadiers lost three-fourths of their men. Of one company not more than five, and of another not more than fourteen, escaped.

The unexpected resistance of the Americans was such as wiped away the reproach of cowardice, which had been cast upon them by their enemies in Britain. The spirited conduct of the British officers merited and obtained great applause; but the provincials were justly entitled to a large share of the glory for having made the utmost exertions of their adversaries necessary to dislodge them from lines which were the work of only a single night.

The Americans lost five pieces of cannon. Their killed amounted to one hundred thirty-nine; their wounded and missing, to three hundred fourteen. Thirty of the former fell into the hands of the conquerors. They particularly regretted the death of General Warren. To the purest patriotism and most undaunted bravery he added the virtues of domestic life, the eloquence of an accomplished orator, and the wisdom of an able statesman. Only a regard for the liberty of his country induced him to oppose the measures of Government. He aimed not at a separation from, but a coalition with, the mother-country.

The burning of Charlestown, though a place of great trade, did not discourage the provincials. It excited resentment and execration, but not any disposition to submit. Such was the high-strung state of the public mind, and so great the indifference of property when put in competition with liberty, that military conflagrations, though they distressed and impoverished, had no tendency to subdue, the colonists. Such means might suffice in the Old World, but were not effectual in the New, where the war was undertaken, not for a change of masters, but for securing essential rights.

The action at Breed’s Hill, or Bunker Hill, as it has since been commonly called, produced many and very important consequences. It taught the British so much respect for the Americans, intrenched behind works, that their subsequent operations were retarded with a caution that wasted away a whole campaign to very little purpose. It added to the confidence the Americans began to have in their own abilities. It inspired some of the leading members of Congress with such high ideas of what might be done by militia, or men engaged for a short term of enlistment, that it was long before they assented to the establishment of a permanent army.

1Charlestown. A body of American riflemen, posted in the houses, galled the left line as it marched; therefore, by Howe’s orders, the town was set on fire.