The Tripolitan War

A.D. 1804

J. FENIMORE COOPER

At the opening of the nineteenth century the United States of America were impelled to resist by force the piratical powers known as the Barbary States, on the northern coast of Africa. These corsairs had long vexed the Mediterranean countries of Europe. Similar annoyances having been suffered by the United States, that country at last inflicted upon one of the offenders-Tripoli-a punishment which proved to be the beginning of the end in the predatory career of all.

During the last years of the eighteenth century the Mediterranean was rendered by these African pirates so unsafe that the merchantships of every nation were in danger of being captured by them, unless protected by an armed convoy or by tribute paid to the Barbary powers. With other countries, the United States had made payments of such tribute, but at last, when an increase of such payments was demanded by Tripoli, the Republic refused to comply. In consequence of this refusal Tripoli, June 10, 1801, declared war against the United States. The conflict which ensued is known as the Tripolitan war. It had been anticipated by the United States, which had already sent a squadron to the Mediterranean. No serious collision took place until October, 1803; then, while chasing a corsair into the harbor of Tripoli, the United States frigate Philadelphia, Captain William Bainbridge, struck a sunken rock, and, being unable to use her guns, was captured by the Tripolitans.

On February 16, 1804, Lieutenant Stephen Decatur, under orders of Commodore Edward Preble, performed what Nelson called "the most daring act of the age," which made the young officer one of the most famous among naval heroes. With a captured Tripolitan craft, renamed the Intrepid, and a crew of seventy-five men, he entered the harbor of Tripoli by night, boarded the Philadelphia, within half gunshot of the pacha’s castle, drove the Tripolitan crew overboard, set the ship on fire, remained alongside until the flames were beyond control, and then withdrew without losing a man," though under the fire of one hundred forty-one guns.

The further operations and end of the war are narrated by Cooper, who, although most widely known by his novels, was himself at one time an officer in the United States Navy. of which he is also one of the best historians.

IT was July 21, 1804, when Commodore Preble was able to sail from Malta, with all the force he had collected, to join the vessels cruising off Tripoli. The blockade had been kept up with vigor for some months, and the Commodore felt that the season had now arrived for more active operations. He had with him the Constitution, Enterprise, Nautilus, two bomb-vessels, and six gunboats. The bomb-vessels were of only thirty tons measurement, and carried a thirteen-inch mortar each. In scarcely any respect were they suited for the duty that was expected of them. The gunboats were little better, being shallow, unseaworthy craft, of about twenty-five tons burden, in which long iron twenty-fours had been mounted. Each boat had one gun and thirty-five men; the latter, with the exception of a few Neapolitans, being taken from the different vessels of the squadron. The Tripolitan gunboats were altogether superior, and the duty should have been exactly reversed, in order to suit the qualities of the respective craft; the boats of Tripoli having been built to go on the coast, while those possessed by the Americans were intended solely for harbor defence. In addition to their other bad qualities, these Neapolitan boats were found neither to sail nor to row even tolerably well. It was necessary to tow them by larger vessels the moment they got into rough water, and when it blew heavily there was always danger of dragging them under. In addition to this force, Commodore Preble had obtained six long twenty-six pounders for the upper-deck of the Constitution, which were mounted in the waist.

When the American commander assembled his whole force before Tripoli, on July 25, 1804, it consisted of the Constitution 44 guns, Commodore Preble; Siren 16, Lieutenant-Commandant Stewart; Argus 16, Lieutenant-Commandant Hull; Scourge 14, Lieutenant-Commandant Dent; Vixen 12, Lieutenant-Commandant Smith; Nautilus 12, Lieutenant-Commandant Somers; Enterprise 12, Lieutenant-Commandant Decatur; the two bomb-vessels, and six gunboats. In some respects this was a well-appointed force for the duty required, while in others it was lamentably deficient. Another heavy ship, in particular, was wanted, and the means for bombarding had all the defects that may be anticipated. The two heaviest brigs had armaments of twenty-four-pound carronades; the other brig, and two of the schooners, armaments of eighteen-pound carronades; while the Enterprise retained her original equipment of long sixes in consequence of her ports being unsuited to the new guns.

As the Constitution had a gun-deck battery of thirty long twenty-fours, with six long twenty-sixes, and some lighter long guns above, it follows that the Americans could bring twenty-two twenty-fours and six twenty-sixes to bear on the stone walls of the town, in addition to a few light chase-guns in the small vessels, and the twelve-pounders of the frigate’s quarter-deck and forecastle. On the whole, there appears to have been in the squadron twenty-eight heavy long guns, with about twenty lighter, that might be brought to play on the batteries simultaneously. Opposed to these means of offence, the pacha had one hundred fifteen guns in battery, most of them quite heavy, and nineteen gunboats that, of themselves, so far as metal was concerned, were nearly equal to the frigate. Moored in the harbor were also two large galleys, two schooners, and a brig, all of which were armed and strongly manned. The American squadron was manned by one thousand sixty persons, all told, while the pacha had assembled a force that has been estimated as high as twenty-five thousand, Arabs and Turks included. The only advantage possessed by the assailants, in the warfare that was so soon to follow, were those which are dependent on spirit, discipline, and system.

The vessels could not anchor until the 28th, when they ran in, with the wind at east-southeast, and came to, by signal, about a league from the town. This was hardly done, however, before the wind came suddenly round to north-northwest, thence north-northeast, and it began to blow strong, with a heavy sea setting directly on shore. At 6 P.M. a signal was made for the vessels to weigh and to gain an offing. Fortunately the wind continued to haul to the eastward, or there would have been great danger of towing the gunboats under while carrying sail to claw off the land. The gale continued to increase until the 31st, when it blew tremendously. The courses of the Constitution were blown away, though reefed, and it would have been impossible to save the bomb-vessels and gunboats had not the wind hauled so far to the southward as to give smooth water. Fortunately, the gale ceased the next day.

On August 3, 1804, the `squadron ran in again and got within a league of the town, with a pleasant breeze at the eastward. The enemy’s gunboats and galleys had come outside of the rocks and were lying there in two divisions; one near the eastern and the other near the western entrance, or about half a mile apart. At the same time it was seen that all the batteries were manned, as if an attack was not only expected but invited.

At 12:30, noon, the Constitution wore with her head off shore, and showed a signal for all vessels to come within hail. Each commander, as he came up, was ordered to prepare to attack the shipping and batteries. The bomb-vessels and gunboats were immediately manned, and such was the high state of discipline in the squadron that in one hour everything was ready for the contemplated service. On this occasion Commodore Preble made the following distribution of that part of his force which was manned from the other vessels of his squadron:

One bomb-ketch was commanded by Lieutenant-Commandant Dent, of the Scourge. The other bomb-ketch was commanded by Mr. Robinson, first lieutenant of the Constitution.

First division of gunboats. (1) Lieutenant-Commandant Somers, of the Nautilus: (2) Lieutenant James Decatur, of the Nautilus: (3) Lieutenant Blake, of the Argus.

Second division of gunboats. (4) Lieutenant-Commandant Decatur, of the Enterprise: (5) Lieutenant Bainbridge, of the Enterprise: (6) Lieutenant Trippe, of the Vixen.

At half-past one the Constitution wore again, and stood toward the town. At two the gunboats were cast off, and formed in advance, covered by the brigs and schooners, and half an hour later the signal was shown to engage. The attack was commenced by the two bombards, which began to throw shells into the town. It was followed by the batteries, which were instantly in a blaze, and then the shipping on both sides opened their fire, within reach of grape.

The eastern, or most weatherly division of the enemy’s gun-boats, nine in number, as being least supported, was the aim of the American gunboats. But the bad qualities of the latter craft were quickly apparent, for as soon as Decatur steered toward the enemy with an intention to come to close quarters, the division of Somers, which was a little to leeward, found it difficult to sustain him. Every effort was made by the latter officer to get far enough to windward to join in the attack; but finding it impracticable he bore up and ran down alone on five of the enemy to leeward and engaged them all within pistol-shot, throwing showers of grape, cannister, and musket-balls among them. In order to do this, as soon as near enough, the sweeps were got out and the boat was backed astern to prevent her from drifting in among the enemy. The gunboat, Number Three, was closing fast, but a signal of recall being shown from the Constitution she hauled out of the line to obey, and losing ground kept more aloof, firing at the boats and shipping in the harbor; while Number Two, Lieutenant James Decatur, was enabled to join the division to windward. Number Five, Lieutenant Bainbridge, lost her lateen-yard, while still in tow of the Siren, but, though unable to close, she continued advancing, keeping up a heavy fire, and finally touched on the rocks.

By these changes, Lieutenant-Commandant Decatur had three boats that dashed forward with him, though one belonged to the division of Lieutenant-Commandant Somers; viz., Number Four, Number Six, and Number Two.

The officers in command of these three boats went steadily on until within the smoke of the enemy. Here they delivered their fire, throwing in a terrible discharge of grape and musket-balls, and the order was given to board. Up to this moment the odds had been as three to one against the assailants; and they were now, if possible, increased. The brigs and schooners could no longer assist. The Turkish boats were not only the heaviest and the best in every sense, but they were much the strongest manned. The combat now assumed a character of chivalrous effort and of desperate personal prowess that belongs rather to the Middle Ages than to struggles of our own time. Its details, indeed, savor more of the tales of romance than of harsh reality, such as we are accustomed to associate with acts of modern warfare.

Lieutenant-Commandant Decatur took the lead. He had no sooner discharged his volley of musket-balls than Number Four was laid alongside of the opposing boat of the enemy. He boarded her, followed by Lieutenant Thorn M’Donough and all the Americans of his crew. The Tripolitan boat was divided nearly in two parts by a long open hatchway, and as the crew of Number Four came in one side the Turks retreated to the other, making a sort of ditch of the open space. This caused an instant of delay, and perhaps fortunately, for it permitted the assailants to act together. As soon as ready, Decatur charged round each end of the hatchway, and after a short struggle a part of the Turks were piked and bayoneted, while the rest submitted or leaped into the water.

No sooner had Decatur got possession of the boat first assailed than he took her in tow and bore down on the one next to leeward. Running the enemy aboard, as before, he boarded him with the most of his officers and men. The captain of the Tripoli-tan vessel was a large powerful man and Decatur charged him with a pike. The weapon, however, was seized by the Turk, wrested from the hands of the assailant, and turned against its owner. The latter parried a thrust, and made a blow with his sword at the pike, with a view to cut off its head. The sword hit the iron and broke at the hilt and the next instant the Turk made another thrust. The gallant Decatur had nothing to parry the blow but his arm, with which he so far avoided it as to receive the pike only through the flesh of his breast. Tearing the iron from the wound he sprang within the Turk’s guard and grappled his antagonist. The pike fell between the two and a short trial of strength succeeded, in which the Turk prevailed. As the combatants fell, however, Decatur so far released himself as to lie side by side with his foe on the deck. The Tripolitan now endeavored to reach his poniard while his hand was firmly held by that of his enemy. At this critical instant, when life or death depended on a moment well employed or a moment lost, Decatur drew a small pistol from the pocket of his vest, passed the arm that was free round the body of the Turk, pointed the muzzle in, and fired. The ball passed entirely through the body of the Mussulman and lodged in the clothes of his foe. At the same instant Decatur felt the grasp that had almost smothered him relax, and he was liberated. He sprang up and the Tripolitan lay dead at his feet.

In such a melee it cannot be supposed that the struggle of the two leaders would go unnoticed. An enemy raised his sabre to cleave the skull of Decatur while he was occupied with his enemy, and a young man of the Enterprise’s crew interposed an arm to save him. The blow was intercepted, but the limb was severed, leaving it hanging only by a bit of skin. A fresh rush was now made upon the enemy, who was overcome without much further resistance.

An idea of the desperate nature of the fighting that distinguished this remarkable assault may be gained from the amount of the loss. The two boats captured by Lieutenant-Commandant Decatur had about eighty men in them, of whom fifty-two were known to have been killed and wounded, most of the latter very badly. As only eight prisoners were made who were not wounded, and many jumped overboard and swam to the rocks, it is not improbable that the Turks suffered still more severely. Lieutenant-Commandant Decatur himself being wounded, he secured his second prize and hauled off to rejoin the squadron, all the rest of the enemy’s division that were not taken having by this time run into the harbor by passing through the openings between the rocks.

When Lieutenant-Commandant Decatur was thus employed to windward, his brother, Lieutenant James Decatur, the first lieutenant of the Nautilus, was nobly emulating his example in Number Two. Reserving his fire, like Number Four, this young officer dashed into the smoke, and was on the point of boarding when he received a musket-ball in his forehead. The boats met and rebounded; and in the confusion of the death of the commanding officer of Number Two, the Turk was enabled to escape, under a heavy fire from the Americans. It was said, at the time, that the enemy had struck before Lieutenant Decatur fell, though the fact must remain in doubt. It is, however, believed that he sustained a very severe loss.

In the mean time, Lieutenant Trippe in Number Six, the last of the three boats that were able to reach the weather division, was not idle. Reserving his fire like the others, he delivered it with deadly effect when closing, and went aboard his enemy in the smoke. In this instance the boats also separated by the shock of the collision, leaving Lieutenant Trippe, with J. D. Henley and nine men only, on board the Tripolitan. Here, too, the commanders singled each other out, and a fierce personal combat occurred while the work of death was going on around them. The Turk was young and of large and athletic build, and soon compelled his slighter but more active foe to fight with caution. Advancing on Lieutenant Trippe he would strike a blow and receive a thrust in return. Th this manner he gave the American commander no less than eight sabre wounds in the head and two in the breast; when making a sudden rush he struck a ninth blow on the Lieutenant’s head which brought him down upon one knee. Rallying all his force in a desperate effort the latter, who still retained the short pike with which he fought, made a thrust that forced the weapon through the body of his gigantic adversary and tumbled him on his back. As soon as the Tripolitan officer fell the remainder of his crew surrendered.

The boat taken by Lieutenant Trippe was one of the largest belonging to the pacha. The number of her men is not positively known, but, living and dead, thirty-six were found in her, of whom twenty-one were either killed or wounded. When it is remembered that but eleven Americans boarded her the achievement must pass for one of the most gallant on record. All this time the cannonading and bombardment continued without ceasing. Lieutenant-Commandant Somers, in Number one, sustained by the, brigs and schooners, had forced the remaining boats to retreat, and this resolute officer pressed them so hard as to be compelled to wear within a short distance of a battery of twelve guns close to the mole. Her destruction seemed inevitable. As the boat came slowly round, a shell fell into the battery and most opportunely blew up the platform, driving the enemy out to the last man. Before the guns could be again used, the boat had got in tow of one of the small vessels.

There was a division of five boats and two galleys of the enemy that had been held in reserve within the rocks, and these rallied their retreating countrymen and made two efforts to come out and intercept the Americans and their prizes; but they were kept in check by the fire of the frigate and small vessels. The Constitution maintained a very heavy fire and silenced several of the batteries, though they reopened as soon as she had passed. The bombards were covered with the spray of shot, but continued to throw shells to the last. At half past four the wind coming round to the northward a signal was made for the gunboats and bomb-ketches to rejoin the small vessels, and another to take them and the prizes in tow. The last order was handsomely executed by the brigs and schooners under cover of a blaze of fire from the frigate. A quarter of an hour later the Constitution herself hauled off and ran out of gunshot.

Thus terminated the first serious attack that was made on the town and batteries of Tripoli. Its effect on the enemy was of the most salutary kind, the manner in which their gunboats had been taken by boarding making a deep and lasting impression. The superiority of the Americans in gunnery was generally admitted before, but here was an instance in which the Turks had been overcome by inferior number, hand to hand, a kind of conflict in which they had been thought particularly to excel. Perhaps no instance of more desperate fighting of the sort, without defensive armor, is to be found in the pages of history. Three gunboats were sunk in the harbor in addition to the three that were taken; and the loss of the Tripolitans by shot must have been very heavy. About fifty shells were thrown into the town, but little damage appears to have been done in this way; very few of the bombs-on account of the imperfect materials that had been furnished-exploding. The batteries were considerably damaged, but the town itself suffered no material injury.

On the American side only fourteen were killed and wounded in the affair; and all of these, with the exception of one man, belonged to the gunboats. The Constitution, though under fire two hours, escaped much better than could have been expected. She received one heavy shot through her mainmast, had a quarterdeck gun injured, and was a good deal cut up aloft. The enemy had calculated his range for a more distant cannonade and generally overshot the ships. By this mistake the Constitution had her main royal yard shot away.

The pacha now became more disposed than ever to treat, the warfare promising much annoyance with no corresponding benefits. The cannonading did his batteries and vessels great injury, though the town probably suffered less than might have been expected, being in a measure protected by its walls. The shells, too, that had been procured at Messina turned out to be very bad, few exploding when they fell. The case was different with the Thot, which did effective work on the different batteries. Some idea may be formed of the spirit of the last attack from the report of Commodore Preble, who stated that nine guns, one of which was used but a short time, threw five hundred heavy shot in the course of little more than two hours. Although the delay, caused by the expected arrival of the reenforcement, was used to open a negotiation, it was without effect. The pacha had lowered his demands one-half, but he still insisted on a ransom of five hundred dollars a man for his prisoners, though he waived the usual claim for tribute in future. These propositions were not received, it being expected that, after the arrival of the reenforcement, the treaty might be made on the usual terms of civilized nations.

On August 9th the Argus, Captain Hull, had a narrow escape. That brig having stood in toward the town to reconnoitre, with Commodore Preble on board, one of the heaviest of the shot from the batteries raked her bottom for some distance and cut the planks half through. An inch or two of variation in the direction of this shot would infallibly have sunk the brig, and that probably in a few minutes.

No intelligence arriving from the expected vessels, Commodore Preble, about the 16th, began to make his preparations for another attack, sending the Enterprise, Lieutenant-Commandant Robinson, to Malta with orders for the agent to forward transports with water, the vessels being on a short allowance. On the night of the 17th, Captains Decatur and Chauncey went close in, in boats, and reconnoitred the situation of the enemy. These officers on their return reported that the vessels of the Tripolitan flofilla were moored abreast of each other, from a line extending from the mole to the castle, with their heads to the eastward, making a defence directly across the inner harbor or galley-mole. A gale, however, compelled the American squadron to stand off shore on the morning of the 18th, causing another delay in the contemplated movements. While lying-to in the offing the vessels met the transports from Malta, and the Enterprise returned bringing no intelligence from the expected reenforcement.

On the 24th the squadron stood in toward the town again, with a light breeze from the eastward. At 8 P.M. the Constitution anchored just out of gunshot of the batteries, but it fell calm and the boats of the different vessels were sent to tow the bombards to a position favorable for throwing shells. This was thought to have been effected by 2 A.M., when the two vessels began to throw their bombs, covered by the gunboats. At daylight they all retired without having received a shot in return. Commodore Preble appears to have distrusted the result of this bombardment, the first attempted at night, and there is a reason to think it had but little effect.

The weather proving very fine and the wind favorable, on the 28th Commodore Preble determined to make a more vigorous assault on the town and batteries than any which had preceded it, and his dispositions were taken accordingly. The gunboats and bombards requiring so many men to manage them, the Constitution and the small vessels had been compelled to go into action short of hands in the previous affairs. To obviate this difficulty, the John Adams had been kept before the town, and a portion of her officers and crew, and nearly all her boats, were now put in requisition. Captain Chauncey himself, with about seventy of his people, went on board the flagship, and all the boats of the squadron were hoisted out and manned. The bomb-vessels were crippled and could not be brought into service, a circumstance that probably was of no great consequence on account of the poor ammunition they were compelled to use. These two vessels, with the Scourge, transports, and John Adams, were anchored well off at sea, not being available in the contemplated carnonading.

Everything being prepared, a little after midnight the following gunboats proceeded to the stations, viz., Number one, Captain Somers; Number Two, Lieutenant Gordan; Number Three, Mr. Brooks, master of the Argus; Number Four, Captain Decatur; Number Five, Lieutenant Lawrence; Number Six, Lieutenant Wadsworth; Number Seven, Lieutenant Crane; Number Nine, Lieutenant Thorne. They were divided into two divisions as before, Captain Decatur having become a superior officer, however, by his recent promotion. About 3 A.M. the gunboats advanced close to the rocks at the entrance of the harbor, covered by the Siren, Captain Stewart; Argus, Captain Hull; Vixen, Captain Smith; Nautilus, Lieutenant-Commandant Robinson, and accompanied by all the boats of the squadron. Here they anchored, with springs on their cables, and commenced a cannonade en the enemy’s shipping, castle, and town. As soon as the day dawned the Constitution weighed anchor and stood in toward tee rocks, under a fire from the batteries, Fort English, and the castle. At this time the enemy’s gunboats and galleys, thirteen in number, were closely and warmly engaged with the eight American boats; and the Constitution, ordering the latter to retire by signal, as their ammunition was mostly consumed, delivered a heavy fire of round and grapeshot on the former as she came up. One of the enemy’s boats was soon sunk, two were run ashore to prevent them from meeting a similar fate, and the rest retired.

The Constitution now continued to stand on until she had run in within musket-shot of the mole, when she brought up, and opened upon the town, batteries, and castle. Here she lay three-quarters of an hour, pouring in a fierce fire with great effect, until, finding that all the small vessels were out of gunshot, she hauled off. About seven hundred heavy shot were thrown at the enemy in this attack, besides a good many from the chase-guns of the small vessels. The enemy sustained much damage and lost many men. The American brigs and schooners were a good deal injured aloft, as was the Constitution. Although the latter ship was so long within reach of grape, many of which shot struck her, she had not a man hurt. Several of her shrouds, backstays, trusses, springstays, chains, lifts, and a great deal of running rigging were shot away, and yet her hull escaped with very trifling injuries. A boat belonging to the John Adams, under the orders of John Orde Creighton, one of that shipmaster’s mates, was sunk by a double-headed shot which killed three men and badly wounded a fourth, but the officer and the rest of the boat’s crew were saved.

In this attack a heavy shot from the American gunboats struck the castle, passed through a wall, and rebounding from the opposite side of the room fell within six inches of Captain Bainbridge, who was in bed at the time, and covered him with stones and mortar, from under which he was taken, badly injured, by his officers. More harms was done the town in this attack than in either of the others, the shot appearing to have struck many of the houses. From this time to the close of the month preparations were made to use the bombards again and to renew the cannonading. Another transport arrived from Malta, but without bringing any intelligence of the vessels under the orders of Commodore Barron. On September 3rd, everything being ready, at half past two the signal was’ given for the small vessels to advance. The enemy had improved the time as well as the Americans; they had raised three of their own gunboats that had been sunk in the engagements of August 3rd and 28th. These craft were now added to the rest of their flotilla.

The Tripolitans had also changed their mode of fighting. Hitherto, with the exception of the battle of August 3rd, their galleys and gunboats had lain either behind the rocks in position to fire over them, or at the openings between them, and they consequently found themselves to leeward of the frigate and small American cruisers, the latter invariably choosing easterly winds to advance with, as such would permit crippled vessels more quickly to retire. On August 3rd (the case above excepted), the Turks had been so roughly used when brought to a hand-to-hand struggle-when they evidently expected nothing more than a cannonade-that they were not disposed to venture again outside of the harbor. On September 3rd, however, their plan of defence was more judiciously offered. No sooner was it perceived that the American squadron was in motion with the design to attack them than the gunboats and galleys got under way and worked up to windward until they gained a point on the weather side of the harbor, being directly under the fire of Fort English as well as of a new battery that had been erected a little to the westward of the latter.

This disposition of the enemy’s force required a corresponding change on the part of the Americans. The bombards were directed to take stations and to commence throwing their shells; while the gunboats in two divisions, commanded as usual by Captains Decatur and Somers and protected by the guns of the brigs and schooners, assailed the enemy’s flotilla. This arrangement separated the battle into two distinct parts, leaving the bomb-vessels very much exposed to the fire of the castle, the mole, crown, and other batteries. The Tripolitan gunboats and galleys stood the fire’ of the American flotilla until the latter had got within musketry-shot, when they retired. The assailants then separated, some of the gunboats following the enemy and pouring in their fire, while the others, with the brigs and schooners, cannonaded Fort English.

In the mean while, perceiving that the bombards were suffering severely from the continuous fire of the guns to which they were exposed, Commodore Preble ran down the Constitution close to the rocks and the bomb-vessels, and brought-to. Here the frigate opened as warm a fire as probably ever came out of a single-decked ship. She was, moreover, in a position where seventy heavy guns could bear upon her. The whole harbor in the vicinity of the town was glittering with the spray of her shot, and each battery, as usual, was silenced as soon as it drew her attention. After throwing more than three hundred round shot, besides grape and cannister, the frigate hauled off, having previously ordered the other vessels to retire from action, by signal. The gunboats in this affair were an hour and fifteen minutes engaged, in which time they threw four hundred round shot besides grape and cannister: Lieutenant Trippe, who had so much distinguished himself and had received so many wounds on August 3rd, resumed the command of Number Six, for this occasion. Lieutenant Morris, of the Argus, was in charge of Number Three. As usual, all the small vessels suffered aloft, and the Argus sustained some damage to her hull.

The Constitution was so much exposed in the attack that her escape can only be attributed to the effect of her own heavy fire. It had been found in the previous engagements that so long as she could play-upon a battery the Turks could not be kept at its guns; and it was chiefly while she was veering, or tacking, that she suffered. But after making every allowance for the effect of her own cannonading and for the imperfect gunnery of the enemy, it was astonishing that a single frigate could lie exposed to the fire of more than double her own number of available guns, and these, too, mostly of heavier metal and protected by stone walls. On this occasion the frigate was not supported by the gun-boats, and was the sole object of the enemy’s aim after the bombards had withdrawn.

As might have been expected, the Constitution suffered more in this attack than in any of the previous engagements, though she received nothing larger than grape in her hull. She had three shells through her canvas, one of which rendered the main-topsail temporarily useless. Her sails, standing and running rigging, were also much cut with shot. Captain Chauncey of the John Adams and a party of her officers and crew served in the Constitution again on this day and were of great service. The commander, officers, and crew of the John Adams were always actively employed, although the ship herself could not be brought before the enemy for the want of gun-carriages.

The bombards, being much exposed, suffered accordingly.Number one was so much crippled as to be unable to move without being towed, and was near sinking when she got to the anchorage. Every shroud she had was shot away. Commodore Preble expressed himself satisfied with the good conduct of every man in the squadron. All the vessels appeared to have been well handled and efficient in their several stations.

While Commodore Preble was thus actively employed in carrying on the war against the enemy-this last attack being the fifth made on the town within a month-he had been meditating another maneuvre, and was now ready to put it into execution. The ketch Intrepid, which had been employed by Decatur in burning the Philadelphia, was still in the squadron, having been used of late as a transport between Tripoli and Malta. This vessel had been converted into an "infernal," or, to use more intelligible terms, she had been fitted out as a floating mine, with the intention of sending her into the harbor of Tripoli, to explode among the enemy’s cruisers. Such dangerous work could be confided to none but officers and men of known coolness and courage, of perfect self-possession and of tried spirit. Captain Somers, who had commanded one division of the gunboats in the different attacks on the town in a manner to excite the respect of all who witnessed his conduct, volunteered to take charge of this enterprise; and Lieutenant Wadsworth, of the Constitution, an officer of great merit, offered himself as the second in command.

When the Intrepid was last seen by the naked eye she was not a musket-shot from the mole, standing directly for the harbor. One officer on board the nearest vessel, the Nautilus, is said, however, to have never lost sight of her with a night-glass, but even he could distinguish no more than her dim outlines. There was a vague rumor that she touched on the rocks, though it did not appear to rest on sufficient authority to be entitled to much credit. To the last moment she appeared to be advancing. About that time the batteries began to fire. Their shots are said to have been directed toward every point where an enemy might be expected, and it is not improbable that some were aimed at the ketch.

The period between the time when the Intrepid was last seen and that when most of those who watched without the rocks learned her fate, was not long. This was an interval of intense, almost of breathless expectation; and it was interrupted only by the flashes and the roar of the enemy’s guns. Various reports exist of what those who gazed into the gloom beheld or fancied they beheld; but one melancholy fact alone would seem to be beyond contradiction. A fierce and sudden light illuminated the scene; a torrent of fire streamed upward, and a concussion followed that made the cruisers in the offing tremble from their trucks to their keels. This sudden blaze of light was followed by a darkness of twofold intensity, and the guns of the battery became mute as if annihilated. Numerous shells were seen in the air, and some of them descended on the rocks where they were heard to fall. The fuses were burning and a few exploded, but much the greater part were extinguished in the water. The mast, too, had risen perpendicularly with its rigging and canvas blazing, but the descent was veiled in the blackness that followed.

So sudden and tremendous was the eruption, and so intense the darkness which succeeded, that it was not possible to ascertain the precise position of the ketch at the moment. In the glaring but fleeting light no person could say that he had noted more than the material circumstance that the Intrepid had not reached the point at which she aimed. The shells had not spread far, and those which fell on the rocks were so many proofs of this important fact. There was nothing else to indicate the precise spot where the ketch exploded. A few cries arose from the town, but the deep silence that followed was more eloquent than any clamor. The whole of Tripoli was like a city of tombs.

If every eye had been watchful previous to the explosion, every eye now became doubly vigilant to discover the retreating boats. Men got over the sides of the vessel, holding lights and placing their ears near the water in the hope of detecting the sounds of even muffled oars; and often it was fancied that the gallant adventurers were near. They never reappeared. Hour after hour went by until hope became exhausted. Occasionally-rocket gleamed in the darkness, or a sullen gun was heard from the frigate as a signal to the boats; but the eyes that should have seen the first were sightless, and the sound of the last fell on the ears of the dead.

The three vessels assigned to that service hovered around the harbor until the sun rose; but few traces of the Intrepid, and nothing of her devoted crew, could be discovered. The wreck of the mast lay on the rocks near the western entrance, and here and there a fragment was visible near it. One of the largest of the enemy’s gunboats was missing, and it was observed that two others which appeared to be shattered were being hauled upon the shore. The three that had lain across the entrance had disappeared. It was erroneously thought that the castle had sustained some injury from the concussion, but on the whole, the Americans were left with the melancholy certainty of having met with a serious loss without obtaining any commensurate advantage.

A sad and solemn mystery, after all our conjectures, must forever veil the fate of those fearless officers and their hardy followers. In whatever light we view the affair they were the victims of that self-devotion which causes the seaman and soldier to hold his life in his hand when the honor or interest of his country demands the sacrifice. The name of Somers has passed into a battle-cry in the American marine, while those of Wadsworth and Israel are associated with all that can ennoble intrepidity, coolness, and daring.

The war, in one sense, terminated with this scene of sublime destruction. Commodore Preble had consumed so much of his powder in the previous attacks that it was no longer in his power to cannonade; and the season was fast getting to be dangerous to remain on that exposed coast. The country fully appreciated the services of Commodore Preble. He had united caution and daring in a way to denote the highest military qualities; and his success in general had been in proportion. The attack of the Intrepid, the only material failure in any of his enterprises, was well arranged, and had it succeeded it would probably have brought peace in twenty-four hours. As it was, the pacha was well enough disposed to treat, though he seems to have entered into some calculations in the way of money that induced him to hope that the Americans would yet reduce their policy to the level of his own, and prefer paying ransom to maintaining cruisers so far from home. Commodore Preble, and all the officers and men under his orders, received the thanks of Congress, and a gold medal was bestowed on him. By the same resolution Congress expressed the sympathy of the nation in behalf of the relatives of Captain Richard Somers, Lieutenants Henry Wadsworth, James Decatur, James R. Caldwell, Joseph Israel, and John Sword Dorsey, midshipman, the officers killed off Tripoli.

Negotiations for peace now commenced in earnest, Mr. Lear having arrived off Tripoli for that purpose in the Essex, Captain Barron. After the usual intrigues, delays, and prevarications, a treaty was signed on June 3, 1805. By this treaty, no tribute was to be paid in future, but the sum of sixty thousand dollars was given by America for the ransom of the remaining prisoners after exchanging the Tripolitans in her power man for man.

Thus terminated the war with Tripoli after a duration of four years. It is probable that the United States would have retained in service some officers and would have kept up a small force had not this contest occurred; but its influence on the fortunes and character of the navy was incalculable. It saved the first, in a degree at least, and it may be said to have formed the last.

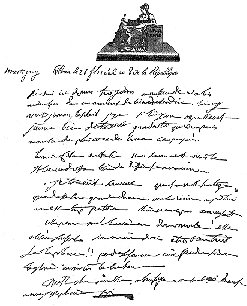

Facsimile of a letter from Napoleon to Josephine