|

|

Messages and Papers of the Presidents, Woodrow Wilson

Contents:

Messages and Papers of the Presidents

WOODROW WILSON

Messages, Proclamations, Executive Orders, and

Addresses to Congress and the People

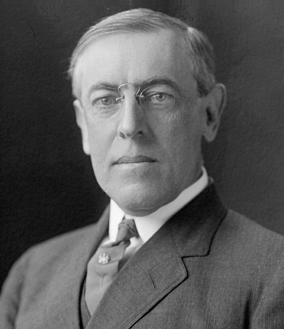

THOMAS WOODROW WILSON, twenty-eighth President of the United States, was known as a jurist, educator, historian, and man of letters before entering political life. He was born in Staunton, Va., Dec. 28, 1856. His mother, Jessie Woodrow, was a native of Carlisle, England. His father, Joseph R., a well-known minister of the Presbyterian Church South, was born in Steubenville, Ohio, of Scotch ancestry. Woodrow Wilson was educated at Davidson College, in North Carolina, and in the private schools of Augusta, Ga., and Columbia, S. C., and received his collegiate training at Princeton University, where he was graduated in 1879. After a course in law at the University of Virginia he was admitted to the bar and practised before the courts in Atlanta, Ga. (1882-83) , and then entered Johns Hopkins University as a special student in history and politics; in 1885 became instructor in history and politics at Bryn Mawr College (Pa.) ; in 1888 a member of the faculty of Wesleyan University, Middletown, Conn., and in 1890 accepted the chair of jurisprudence at Princeton. Married, June 24, 1885, Helen Louise Axson, of Savannah, Ga., who died on August 6, 1914. On December 18, 1915, Mr. Wilson married Mrs. Edith Bolling Galt.

Wilson’s eminent scholarship was attested by the degrees A.B. (Princeton, 1879) ; A.M. (Princeton, 1882) ; LL.B. (U. of Va., 1882) ; Ph.D. (Johns Hopkins, 1885) ; LL.D. (Wake Forest, 1887; Tulane, 1898; Johns Hopkins, 1902; Rutgers, 1902; U. Of Pa., 1903; Brown, 1903 ; Harvard, 1907 ; Williams, 1908 ; Dartmouth, 1909) ; Litt.D. (Yale, 1901). His literary reputation rests upon "Congressional Government: a Study in American Politics," published in 1885, while a student at Johns Hopkins; "The State: Elements of Historical and Practical Politics," a text-book (1888); "An Old Master, and Other Political Essays" (1889) ; "Division and Reunion, 1829-1889," a sketch of the history of the United States during the period of its greatest development (1893) ; "Mere Literature," a volume of literary and historical papers (1896) ; "George Washington," a historical and biographical study (1896) ; "A History of the American People (5 vols., 1902) ; "The Free Life" (1908) ; "Constitutional Government in the United States" (1908) ; "Civic Problems" (1909). In 1890 he was made professor of jurisprudence and politics at Princeton, which position he held until 1902, when he became president of the University. He was elected Governor of New Jersey in 1910. His record as a State executive won for him the Democratic nomination for President in 1912 and he was elected by a plurality over President Taft and ex-President Roosevelt. Again nominated by the Democrats in 1916, he was re-elected over Charles E. Hughes, Republican.

[p.7868]

The most succinct and discriminating appraisal ever made of Woodrow Wilson was by Senator Williams of Mississippi, when the Senator spoke of the ’President as long-visioned, deep-visioned, and tender-visioned.’

Flung into American politics at a time of confusion and upheaval, where the radical and reactionary elements were trying in vain to diagnose the ills of society and to prescribe the appropriate remedies, Woodrow Wilson by the compelling clarity of his vision brought order out of chaos, fused refractory elements, and with unmistakable directness pointed the inviting paths of a new national life.

For his appointed task the elements in the chief executive were kindly mixed. Though elected from the State of New Jersey, he was sprung of Virginia parentage. While his adult life had rendered him not immune to the pulsing industrial life of the great industrial and manufacturing communities in which his mature lot was cast, his boyhood in the South had kept him alive to the vital and simpler needs and habits of a great agricultural section, all but impoverished by the Civil War, but instinct with the elemental political virtues of the early Republic.

His predilection for public affairs found no congenial vent in the active practice of the law, which he renounced as fast becoming not a profession but a trade. Turning his back on the law he betook himself to the severe apprenticeship of scholarship, and in the unremunerative labor of teaching and writing won for a time a modest livelihood.

In his study of American social and constitutional history his incisive clarity and balance soon challenged attention. At a time when the legal and formalistic study of the text of statutes was supposed to constitute the equipment of the great lawyer and publicist, he boldly challenged this great popular superstition.

While historians almost without exception had theretofore maintained that the doctrine of Federal powers as it was constituted after the Civil War had been the precise idea entertained by the Fathers, he showed convincingly that the earlier balance of opinion had inclined toward the views of state sovereignty; and that it was rather the weight of experience and commercial evolution which bad made national supremacy imperative; and that Webster, the great expounder of the Constitution, was right, not as a historian but primarily as a prophet.

When the doctrine of checks and balances in government and the three-fold division of governmental powers were supposed to constitute almost a divine revelation in the political art, he stoutly insisted that the Constitution is not reverenced by blind worship.

When the separation of governmental powers,-the much lauded opposition of the executive to the legislature, and of both to the judiciary,-was mistakenly interpreted as the last perfection of the science of government, he demonstrated that it divided and scattered responsibility, precluded the harmonious functioning of administration, beclouded the popular understanding of the politics; and that the fear of a fanciful tyranny had made for the real supremacy of the invisible government of an irresponsible machine. [p.7866]

The growth of the common law he had early appraised at its real value as the gradual development of policy to subserve and accommodate the real but changing needs of the people. His sudden emergence into the politics of his adopted state and his elevation to the governorship were signalized by a reconstitution of industrial law under his compelling leadership. The workman’s compensation act and similar legislation, and the relegation of private and corporate interests to effective legal control in the interest of the commonwealth, transformed the policy of the state.

Elected to the presidency in anticipation of effectuating a constructive policy of domestic reforms, he encountered at the very outset the menace of serious foreign complications.

The knowledge of the scholar, however, was not in his case sicklied o’er with the pale cast of hesitation or dismay. His adherents in Congress were welded together into a cohesive legion of harmonious and "forward looking" supporters. The long deferred and complex program of establishing a scientific banking and currency law was pushed to successful conclusion. Revenue legislation was reshaped with the intent of exorcising therefrom the last lurking vestiges of privilege to special interests. And our great Federal Charter, the Constitution, was invigorated by freeing the Federal government from hampering limitations upon the raising of revenue by income taxation; and by placing the choice of United States senators directly in the hands of the electorate.

In Mexico the President set himself resolutely to prevent interference in the domestic chaos which vexed and rent that unhappy country. The influence of alien interests with Mexican investments failed to swerve him from his resolve; and whatever the criticism evolved, his policy has cemented the friendship and won the confidence of the South American republics.

While the cloud to the south still hung ominous, the cataclysm of the European struggle burst upon the world. Here again the forceful will of the executive insisted upon absolute neutrality. The infraction of neutral rights by both belligerents, the intrigues of numberless factions seeking to involve the nation in the world conflict on one side or the other, have found the executive adamantine. With patient resolution but with no less stern and persistent resolve for the maintenance of the status of International Law, he has pursued the course he marked out from the start; and while the revelations of the conflict have shown the technical complexity of the modern art of warfare and the necessity for timely preparation m case it is honorably unavoidable, the unmistakable ideal of the President is adequate preparedness not for the prosecution of strife, but for the maintenance of lasting Peace.

Contents:

Chicago:

Woodrow Wilson, "Woodrow Wilson," Messages and Papers of the Presidents, Woodrow Wilson, ed. and trans. James D. Richardson in Messages and Papers of the Presidents, Woodrow Wilson Original Sources, accessed October 30, 2025, http://originalsources.com/Document.aspx?DocID=G89DDUX5B48G9IK.

MLA:

Wilson, Woodrow. "Woodrow Wilson." Messages and Papers of the Presidents, Woodrow Wilson, edited and translated by James D. Richardson, in Messages and Papers of the Presidents, Woodrow Wilson, Original Sources. 30 Oct. 2025. http://originalsources.com/Document.aspx?DocID=G89DDUX5B48G9IK.

Harvard:

Wilson, W, 'Woodrow Wilson' in Messages and Papers of the Presidents, Woodrow Wilson, ed. and trans. . cited in , Messages and Papers of the Presidents, Woodrow Wilson. Original Sources, retrieved 30 October 2025, from http://originalsources.com/Document.aspx?DocID=G89DDUX5B48G9IK.

|