The Erosion Cycle in the Life of a River

William Morris Davis

Rivers are so long lived and survive with more or less modification so many changes in the attitude and even in the structure of the land, that the best way of entering on their discussion seems to be to examine the development of an ideal river of simple history, and from the general features thus discovered, it may then be possible to unravel the complex sequence of events that leads to the present condition of actual rivers of complicated history.

A river that is established on a new land may be called an original river. It must at first be of the kind known as a consequent river, for it has no ancestor from which to be derived. Examples of simple original rivers may he seen in young plains, of which southern New Jersey furnishes a fair illustration. Examples of essentially original rivers may be seen also in regions of recent and rapid displacement, such as the Jura or the broken country of southern Idaho, where the directly consequent character of the drainage leads us to conclude that, if any rivers occupied these regions before their recent deformation, they were so completely extinguished by the newly made slopes that we see nothing of them now.

Once established, an original river advances through its long life, manifesting certain peculiarities of youth, maturity and old age, by which its successive stages of growth may be recognized without much difficulty. For the sake of simplicity, let us suppose the land mass, on which an original river has begun its work, stands perfectly still after its first elevation or deformation, and so remains until the river has completed its task of carrying away [p.650] all the mass of rocks that rise above its baselevel. This lapse of time will be called a cycle in the life of a river. A complete cycle is a long measure of time in regions of great elevation or of hard rocks; but whether or not any river ever passed through a single cycle of life without interruption we need not now inquire. Our purpose is only to learn what changes it would experience if it did thus develop steadily from infancy to old age without disturbance.

In its infancy, the river drains its basin imperfectly; for it is then embarrassed by the original inequalities of the surface, and lakes collect in all the depressions. At such time, the ratio of evaporation to rainfall is relatively large, and the ratio of transported land waste to rainfall is small. The channels followed by the streams that compose the river as a whole are narrow and shallow, and their number is small compared to that which will be developed at a later stage. The divides by which the side-streams are separated are poorly marked, and in level countries are surfaces of considerable area and not lines at all. It is only in the later maturity of a system that the divides are reduced to lines by the consumption of the softer rocks on either side. The difference between constructional forms and those forms that are due to the action of denuding forces is in a general way so easily recognized, that immaturity and maturity of a drainage area can be readily discriminated. In the truly infantile drainage system of the Red River of the North, the inter-stream areas are so absolutely flat that water collects on them in wet weather, not having either original structural slope or subsequently developed denuded slope to lead it to the streams. On the almost equally young lava blocks of southern Oregon, the well-marked slopes are as yet hardly channeled by the flow of rain down them, and the depressions among the tilted blocks are still undrained, unfilled basins.

As the river becomes adolescent, its channels are deepened and all the larger ones descend close to base level If local contrasts of hardness allow a quick deepening of the down-stream part of the channel, while the part next up-stream resists erosion, a cascade or waterfall results; but like the lakes of earlier youth, it is evanescent, and endures but a small part of the whole cycle of growth; but the falls on the small headwater streams of a large river may last into its maturity, just as there are young twigs on the branches of a large tree. With the deepening of the channels, there comes [p.651] an increase in the number of gulleys on the slopes of the channel; the gulleys grow into ravines and these into side valleys, joining their master streams at right angles (La No qqq and Margerie). With their continued development, the maturity of the system is reached; it is marked by an almost complete acquisition of every part of the original constructional surface by erosion under the guidance of the streams, so that every drop of rain that falls finds a way prepared to lead it to a stream and then to the ocean, its goal. The lakes of initial imperfection have long since disappeared; the waterfalls of adolescence have been worn back, unless on the still young headwaters. With the increase of the number of side-streams, ramifying into all parts of the drainage basin, there is a proportionate increase in the rate of waste under atmospheric forces; hence it is at maturity that the river receives and carries the greatest load; indeed, the increase may be carried so far that the lower trunk-stream, of gentle slope in its early maturity, is unable to carry the load brought to it by the upper branches, and therefore resorts to the temporary expedient of laying it aside in a flood-plain. The level of the flood-plain is sometimes built up faster than the small side-streams of the lower course can fill their valleys, and hence they are converted for a little distance above their mouths into shallow lakes. The growth of the flood-plain also results in carrying the point of junction of tributaries farther and farther down stream, and at last in turning lateral streams aside from the main stream, sometimes forcing them to follow independent courses to the sea (Lombardini). But although thus separated from the main trunk, it would be no more rational to regard such streams as independent rivers than it would be to regard the branch of an old tree, now fallen to the ground in the decay of advancing age, as an independent plant; both are detached portions of a single individual, from which they have been separated in the normal processes of growth and decay.

In the later and quieter old age of a river system, the waste of the land is yielded slower by reason of the diminishing slopes of the valley sides; then the headwater streams deliver less detritus to the main channel, which, thus relieved, turns to its postponed task of carrying its former excess of load to the sea, and cuts terraces in its flood plain, preparatory to sweeping it away. It does not always lind the buried channel again, and perhaps settling down on a low spur a little to one side of its old line, produces a [p.652] rapid or a low fall on the lower slope of such an obstruction (Penck) Such courses may be called locally superimposed.

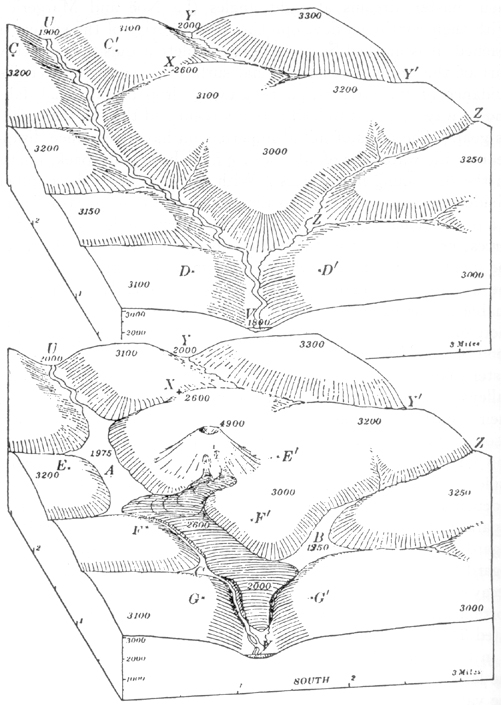

FIG.38.—The first two of a series of eight block diagrams drawn by Davis to illustrate an ideal sequence of events in a volcanic region, c. 1900.

FIG.38.—The first two of a series of eight block diagrams drawn by Davis to illustrate an ideal sequence of events in a volcanic region, c. 1900.

It is only during maturity and for a time before and afterwards that the three divisions of a river, commonly recognized, appear most distinctly; the torrent portion being the still young head-water [p.653] branches, growing by gnawing backwards at their sources; the valley portion proper, where longer time of work has enabled the valley to obtain a greater depth and width; and the lower flood-plain portion, where the temporary deposition of the excess of load is made until the activity of middle life is past.

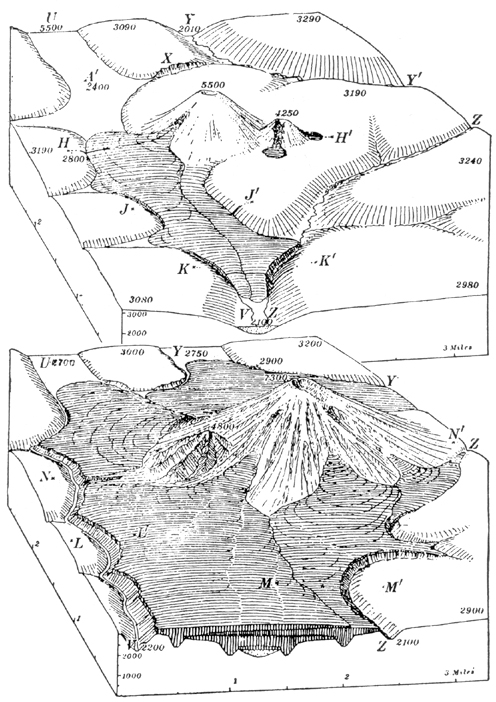

FIG. 39.—The third and fourth diagrams of the series beginning with Fig. 38.

FIG. 39.—The third and fourth diagrams of the series beginning with Fig. 38.

[p.654] Maturity seems to be a proper term to apply to this long enduring stage; for as in organic forms, where the term first came into use, it here also signifies the highest development of all functions between a youth of endeavor towards better work and an old age of relinquishment of fullest powers. It is the mature river in which the rainfall is best led away to the sea, and which carries [p.655] with it the greatest load of land waste; it is at maturity that the regular descent and steady flow of the river is best developed, being the least delayed in lakes and least overhurried in impetuous falls.

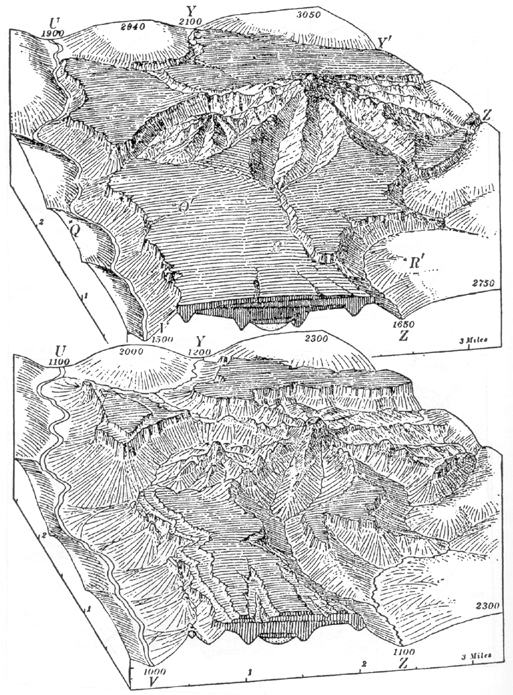

FIG. 40.—The fifth and sixth diagrams of the series beginning with Fig. 38.

FIG. 40.—The fifth and sixth diagrams of the series beginning with Fig. 38.

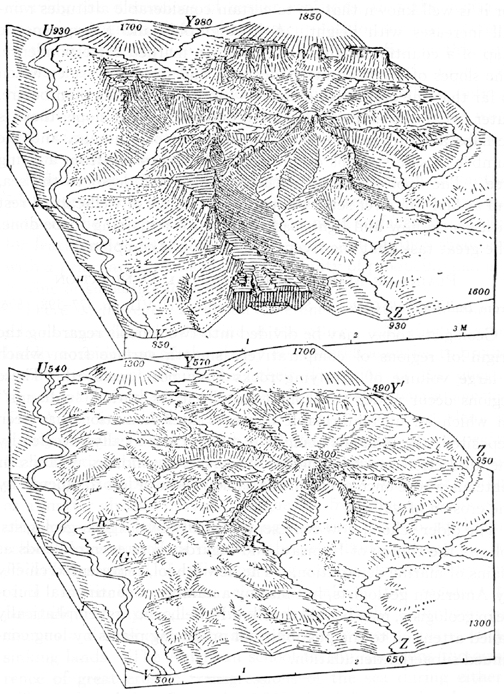

FIG. 41.—The last two diagrams of the series beginning with Fig. 38.

FIG. 41.—The last two diagrams of the series beginning with Fig. 38.

Maturity past, and the power of the river is on the decay. The relief of the land diminishes, for the streams no longer deepen their [p.656] valleys although the hill tops are degraded; and with the general loss of elevation, there is a failure of rainfall to a certain extent; for it is well known that up to certain considerable altitudes rainfall increases with height. A hyetographic and a hypsometric map of a country for this reason show a marked correspondence. The slopes of the headwaters decrease and the valley sides widen so far that the land baste descends from them slower than before. Later, what with failure of rainfall and decrease of slope, there is perhaps a return to the early imperfection of drainage, and the number of side streams diminishes as branches fall from a dying tree. The flood-plains of maturity are carried down to the sea, and at last the river settles down to an old age of well-earned rest with gentle flow and light load, little work remaining to be done. The great task that the river entered upon is completed.