Victory Gardens in World War II

"Food will win the war and write the peace," announced Agriculture Secretary Claude Wickard in a statement to the press in early 1943. "We need more food than ever before in history. If a suitable space is not available at home, all who can do so are asked to obtain plots on community or allotment gardens that can be reached by bus or street car."

Even before the United States entered the war in 1941, U.S. farmers were producing at record levels to supply the food needs of the Allies. After the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor, getting food and equipment to our troops strained production and distribution systems to their limits. Farm labor was in short supply as men left for military service. The Office of Civil Defense was given primary responsibility for convincing nonfarm families to produce and preserve some of their food at home.

It was not difficult to generate willingness to participate. Although by the 1940s most people in the United States lived in towns and cities, many felt some romantic nostalgia for the farm life their parents and grandparents had left. Food rationing, begun in 1942 by limiting purchases of coffee and sugar and later expanded to other products, added practical necessity to nostalgia. Patriotic fervor was contagious. Victory Gardens sprang up everywhere, in sunny backyards, vacant lots, and community spaces. Local governments supported the food production effort by reducing water rates, changing zoning laws to allow chickens and rabbits to be kept in town, and passing stronger laws to punish vandalism and theft.

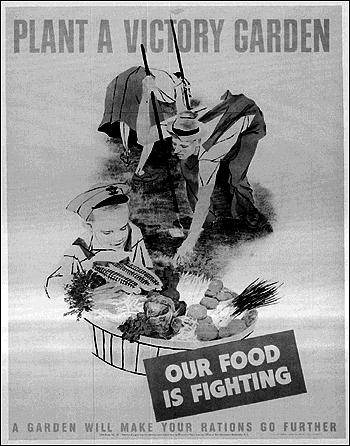

From 1941 until the end of the war, the Office of War Information and the Office of Civil Defense worked with private industry to mount an intensive publicity campaign to promote Victory Gardens. Posters, cartoons, and press releases found in the records of the Office of Civil Defense urged citizens to "Help Uncle plant his garden" in order to "beet" the enemy. Companies like Philco and Standard Oil incorporated Victory Garden encouragement and advice in their newspaper and magazine advertising. The publishers of Better Homes and Gardens financed the production of a short film, "The Gardens of Victory," that was widely shown. Entertainers added Victory Garden comments and jokes to radio scripts, and newspapers were filled with gardening and recipe tips.

Antidote to Mental Depression

Food production was the primary goal of the Victory Garden campaign, but other benefits were cited as incentives. Gardening was promoted as healthy exercise, which would build strength and stamina for whatever lay ahead. Garden work could be a way to fight mental depression. "There’s no quicker way to get your mind off the sordid, horrible side of war than to roll up your sleeves and dig in on a new Victory Garden—no better way to forget about taxes than to plant radishes," said the Pasadena, California, Star-News on August 19, 1943. The article continued: "A Victory Garden...is an admirable defense against the bad effects of too much worry, too much thinking, too much of everything we have all gotten too much of lately."

Another goal is not stated explicitly in the Victory Garden advertising campaign materials in the National Archives, but itdoes appear in the Office of Civil Defense records. These records contain a letter to officials of the Idaho Defense Council from Frank Gaines, Assistant Director for Organization and War Services. Gaines’ letter suggests that youth group garden projects could be an antidote for juvenile delinquency. Young people, he wrote, would find in gardening a good way to channel pent-up aggressive energy into cooperative and productive labor.

Although officials estimated that in many areas one family in three had a food garden, the program was not an unqualified success. Some hastily assembled instruction pamphlets gave advice unsuited to local conditions. The expertise of extension agents at state colleges, an important resource, was not fully recognized or used by backyard farmers. Shortages of equipment and fertilizer combined with adverse weather conditions discouraged many, and the demands of tending a garden through long, hot summer days made gardening less romantic and joyful than at spring planting time. The product sometimes seemed not worth the effort. "Many men particularly, as well as youngsters, think green leafy vegetables are a curse. There is a reason. So often they are served in such a way that they look and taste like steamed hay," complained H.W. Hochbaum in a speech to the Seattle Victory Garden Advisory Council in the summer of 1943. He reported that his survey of gardens in the Chicago area left him encouraged but concerned. "Vacant spaces in these so precious garden plots are slacker spaces and must not be tolerated," he announced.

Despite difficulties, many people worked in the sunshine and managed to grow and preserve a significant part of the family food supply through the war years. But Victory Gardens were a constant reminder of a difficult and painful struggle, a war not yet won. Peace brought higher family incomes, more consumer goods, the end of rationing, and the end of the patriotic fad of victory gardening. Families eagerly embraced the peacetime luxury of processed, packaged, quick-to-fix foods newly available in well-advertised abundance. Not until the back-to-nature movement of the 1960s and the energy crisis of the 1970s would home food gardening again become a popular hobby for millions of Americans.

The poster shown here, "Plant a Victory Garden," is item number 208-PMP-34, Records of the Office of War Information (RG 208), National Archives, Washington, DC. All quotations are found in Civilian War Services Branch, Records of the Office of Civil Defense (RG 171), National Archives, Washington, DC.

Teaching Activities

1. Make a transparency of the poster if this is to be a group activity, or reproduce the poster for individual study and written or oral reporting. Have students list and describe the symbols they see in the poster, both pictorial and written. They should identify and describe the propaganda devices used. What devices promote the idea that garden work is war work? Can you think of ways to change this poster to strengthen the message?

2. Discuss with students the concept of addressing messages to a particular audience. To what segments of the home front public would this poster be most likely to appeal? Who is being encouraged to garden, and why? Who or what group would be likely to plan an ad campaign to convince people to garden today? What are some of government’s concerns today regarding land use? Define a different target audience and design an appropriate pro-garden poster.

3. Not only was food in short supply but so were other resources. Sugar rationing made it difficult for families to preserve the fruit they grew, although extra supplies of sugar were available for canning. Not only was sugar used as food, but it was also made into industrial alcohol needed in the production of synthetic rubber. Why was natural rubber not available? What other essential resources were unavailable or inshort supply? Use maps of World War II to answer these questions.

4. Rationing added to the popularity and utility of Victory Gardens. Have students find out about the rationing program during the war. What goods were rationed? Why? How did the system work?

5. Many people in this country have vivid memories of World War II on the home front. Students should have no difficulty finding family members or family friends who were involved with the Victory Garden program in some way. Have the group plan interview questions in advance; they need to ask specific questions for best results, Consider inviting or visiting people from a nearby garden club or senior center. Consider videotaping or audiotaping the interview, or ask individual students to transcribe their interviews and share them with the class.

6. The government promoted many citizen involvement programs on the home front: collecting and recycling scrap metal and fats, fitting windows with darkening shades for air-raid blackouts, buying war bonds and stamps, and so on. It has been suggested that the government’s real goal was to promote patriotism and war awareness in citizens otherwise relatively untouched by a distant war not yet made present by television, and that civilian defense activities in themselves had little effect on in: creasing usable resources for the war effort. How can students prove or disprove this contention? What kind of data might suggest answers, and where could they get it?

7. Look closely at advertising aimed at shaping civilian participation on the home front in World War II. Locate and bring copies of old newspapers to class for this activity. Ask the students to scan the newspapers and find answers to the questions that follow. Did the government have an interest in maintaining or in changing traditional social patterns and practices in this period? For instance, was it specific government policy to get women to take jobs outside the home during the war and then to go home again when the war ended? Did private custom lead to government policy, or vice versa?