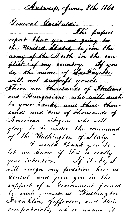

A Letter to Giuseppe Garibaldi

Historical Background

During the early years of the Civil War, the Union Army solicited the aid of experienced foreign officers to lead the untrained, newly recruited troops. The intent was to have these men play much the same role that General Lafayette played during the American Revolution. One such man whom the Union sought was Giuseppe Garibaldi of Italy.

Garibaldi was born July 4, 1807, in Nice, Italy (now a part of France). At a young age he joined the revolutionary forces to fight for the unification of the Italian states and their freedom from Austria. Garibaldi quickly proved himself to be a capable, charismatic leader.

In 1850, after suffering defeat at the hands of the French, Garibaldi fled to America. He was hailed by some Americans as the "Washington of Italy." He returned to Italy in 1854 and rejoined the fight for Italian independence in 1859.

Because of Garibaldi’s ability and persistence as a leader, Secretary of State William H. Seward offered him command of a Union force in 1861. An American diplomat assured Garibaldi that "thousands" of Italian and Hungarian immigrants would be willing to serve under him. In fact, only 17,157 Italians and 3,737 Hungarians lived in the United States at the time. Garibaldi refused the Union offer at first because he thought his military expertise would be needed soon at home. However, the King of Italy, Victor Emmanuel II, gave him permission to go to America if he chose. Garibaldi indicated that he would join the Union Army if he were named Commander in Chief and if the Union would adopt the abolition of slavery as a war goal. The United States would not comply; Lincoln was still hopeful that the Union might be reunited without abolishing slavery. Garibaldi, therefore, refused the offer of a commission.

Garibaldi lived to see Italy united and freed from Austrian rule. He joined the French in their fight against the Prussians in 1870. He retired to his home on the Island of Caprera, in the Tyrrhenian Sea, where he died on June 2, 1882.

Teaching Activities

These activities are varied according to ability levels. Activity 1 is designed for use with students of average to below average reading abilities. It would also be suitable for some junior high students. The worksheet in Activity 1 will help these students achieve success in gathering factual information from a document. Activities 2, 3, and 4 are alternative teaching strategies for students with average to above average reading ability. Any of these activities can be used to build upon Activity 1.

Activity 1: Garibaldi Letter and Worksheet

(Information gathering, reading skills, and copying skills)

1. Make copies of the document (or a transparency for an overhead projector) and of the worksheet, "Letter to Garibaldi," for each student. (This document should reproduce clearly as a Thermofax master.)

2. Provide each student with a copy of the document or project the transparency.

Click the image to view a larger version

Click the image to see a printable, full-page version of this teaching activity

3. Ask a student volunteer to read the letter to the class while other students follow silently.

4. Give each student a copy of the worksheet to complete by using the information in the document. Provide a copy of the document for each student as an exercise in near-point (close) copying, or use a transparency on the overhead projector to practice far-point (distance) copying skills.

Activity 2: Garibaldi’s Job Description

(Oral and written communication skills, creative expression)

1. Tell students to imagine themselves in the following situation:

You are Lincoln’s Secretary of State, William H. Seward, and you have offered Garibaldi a position of leadership with the Union Army. Garibaldi informs you by letter that he is giving serious consideration to the offer. Before making his decision, however, he requests a detailed job description of his duties.

2. Write a job description for Garibaldi. Encourage students to be creative in their job descriptions and to include as many details as they can. You may wish to have your class work in pairs or small groups.

Activity 3: You Were There

(Comparing and contrasting points of view)

1. Begin this activity by discussing with the class the following questions: Would all Union leaders want the aid of an Italian military leader in the Civil War? What factors might shape their points of view?

2. Place the following names on the board: Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States; General George McClellan, Commander of the Union Army; Antonio Enrico, 21-year-old Italian-American draftee.

3. Ask the class to imagine that the year is 1861 and the war has just begun. Ask each student to assume the role of one of the above personalities. Then direct the students to list three reasons why they would or would not support a Union policy of en-

listing the aid of foreign leaders in the cause of the North. Later, ask students to compare and contrast the viewpoints of each person on this issue.

Activity 4: Garibaldi’s Motivation

(Critical thinking)

1. Use the following list to begin a discussion of factors that might have motivated Garibaldi or some other important foreign leader to support the Union cause. (As an alternative approach, ask students to develop their own list of motivations.)

a. To enhance the leader’s glory.

b. To aid an ally in need.

c. To enhance the glory of his or her country in the world’s eyes.

d. To increase personal wealth.

e. To gain support from a country that could help the leader’s country if assistance were needed at a future time.

f. To help eliminate oppression within another country.

g. To gain land or colonies as a reward.

h. To support emigrants from the leaders country who have settled in the warring country.

i. To increase the leader’s influence in his own country.

j. To gain military experience.

2. Ask the class to rank the reasons in order of the importance they may have had in Garibaldi’s decision on whether to enter the Union cause. Encourage students to justify the order of choices, keeping in mind Garibaldi’s various rules as a national leader, a military leader, and an individual. You may want to raise these additional questions: Is there enough evidence available to analyze Garibaldi’s motivations? What other information would be helpful in making a careful assessment?

The letter reproduced here is enclosed in Despatch 20, Quiggle to Secretary of State, July 5, 1861, Despatches from United States Consuls in Antwerp, 1802-1906, Volume 5, General Records of the Department of State, Record Group 59.